|

Imagine yourself as Thomas in John’s Gospel. Jesus, the man you loved, the man you believed would save your people from oppression and tyranny, the man who inspired you to upend your entire life, to leave your home and family behind in order to follow him, is dead. The man you listened to and learned from for three years, the teacher you tried to understand and emulate, this one with whom you lived and travelled this beloved friend, leader, and brother was ripped from your midst, betrayed by another whom you also loved, a shock you’re still reeling from.

The drama began a few weeks ago when Jesus wanted to return to Jerusalem by way of Bethany where his friend Lazarus had died. The other disciples were worried because the Jews in Jerusalem had just tried to stone Jesus, and could easily do so again, and kill him. But you were bold and said, “Let us also go, that we may die with him,” though you never really expected that would happen. You thought everything would be okay. Jesus had evaded authorities and talked his way out of trouble before. You thought he’d do it again. But then, the night of the last dinner you shared together, Jesus who was dear to you, as dear if not more so, than your own twin brother, washed your feet as though he were your servant and said he was leaving with these words: “And if I go and prepare a place for you, I will come again and will take you to myself, so that where I am, there you may be also. And you know the way to the place where I am going.” But you didn’t understand what he meant and answered, “Lord, we do not know where you are going. How can we know the way?” His reply was another one of his all-too-frequent riddles: “I am the way, and the truth, and the life. No one comes to the Father except through me.” After dinner you and the others accompanied him to the garden so he could pray. He asked you to keep watch with him, but you fell asleep and woke up to soldiers and shouting. You drew a sword to protect your beloved leader, but he went with them without protest. Soon everything spun out of control: You scrambled to follow and were swallowed up in an angry mob separated from him. Later the crowds called for his execution and next thing you knew he stumbled up the road to the place of the skull, carrying the cross to which he was soon nailed, where he suffered and died. Perhaps you had the strength to stand alongside his mother and keep watch over your friend in those last agonizing hours of his life. Or perhaps you collapsed in a heap far from the scene and wept over what you knew was coming but couldn’t bear to witness. Whatever you did, the end was the same: Jesus died and left you flattened with grief, and with guilt—why didn’t you try to save him? You cannot fathom any purpose for your life now. Should you go back home and pick up your fishing nets, return to the family you left behind in Galilee? So much has changed in you over the three years you listened to Jesus as he taught and healed, offered hope to outcasts, even sent you and the others out in pairs to spread his message of hope, to invite others to follow. You doubt you can squeeze yourself back into your narrow old life, but how you can possibly carry on when your hope has been slayed and your heart shattered? For three days you stayed here in this locked room with the others. Some thought you were hiding, afraid of arrest by Jewish authorities, afraid you’d be thrown in jail for your association with this Jesus who was crucified for the crime of being King of the Jews. It’s true you were hiding, but it’s not the entire truth. Along with the fear, you were paralyzed by grief and guilt and confusion. You said you’d die with him, but you didn’t even defend him. He is dead and you bear some of the blame. How can you ever make things right? You woke a week ago to Mary Magdalene pounding on the door just after sunrise wild with despair saying Jesus’ body had been stolen. Peter and John went with her to the tomb and came back saying the stone had been rolled away and the linen strips he’d been shrouded in remained behind. None of you could make sense of that, and when, a little while later Mary Magdalene returned saying, “I have seen the Lord,” and told all of you about her encounter in the garden, you thought it was her imagination, wanting him so to return, that she conjured or dreamed him there. For he’d only been gone for three days and you, too, when you closed your eyes still saw Jesus, dreamed of him speaking to the twelve of you gathered around him at a table or a fire, his presence so vivid and comforting that in the first moments after you woke in the mornings, you opened your eyes and scanned the room, expecting to find him there among you. Soon after Mary left again, you left the house too, exhausted after days of confinement in the small house, worrying and mourning together, and then agitated and confused by the frantic conversations among your friends in response to Mary’s news: What had actually happened, what did it mean, what were you all supposed to do next? You walked stealthily through the city for several hours afterward, head bowed, slipping into shadows should you see anyone lest they recognize you as one of Jesus’ disciples, your mind a jumble of thoughts: Why hadn’t you stayed with the women to comfort them as they kept vigil near the tomb? Had soldiers been guarding the tomb? Had they rolled the stone away and carried Jesus’ body with them? And what about the grave clothes? Why would they have unwrapped and left them? It was only a few weeks before when you’d accompanied Jesus to Bethany, after he learned that his friend Lazarus had died. It’d been four days since Lazarus’ death when you arrived, and you’d watched as Jesus called him from the tomb, and Lazarus came stumbling out wrapped in linen strips. Once dead; now alive. It made no sense, but it’d happened. Jesus had made it happen. And if this is what had happened to Jesus, who had called him out of the tomb? Who, other than Jesus, could summon life from death? As you walked night began to fall, and though you’d set out to clear your head, you returned just as confused and to even more commotion. You knocked on the door, one of your friends furtively opened it, ushered you in, and bolted it behind you. Inside, your all friends turned to you and began blurting out the news: “Jesus was here.” “We have seen the lord.” “He lives.” “He appeared in this very room though the doors were locked.” “Twice he said: Peace be with you—He’s never greeted us like that before.” “And it was definitely him, because then he showed us the wounds on his hands, and side.” “He told us to go forth and forgive sins.” “He said, ‘Receive the Holy Spirit,’ and breathed on us.” “I’ve never felt like this before.” “It’s incredible.” The story tumbled from their mouths all at once, the way excited children tell of their discoveries. You asked yourself if Jesus had really been there? How was that possible? Did your friends see a ghost? Were they hallucinating?” You wanted to believe them, but, how could you? You’ve travelled with this crowd, and knew that they were no different than you—human, fallible, followers of Jesus lost without him. And if Jesus had somehow appeared to them from beyond the grave, you wanted with all your heart for him to do the impossible and appear to you, as well. Your friends finished speaking and looked to you for a response and all you could say was, “Before I can believe, I need to experience it for myself… I need to see the mark of the nails in his hands, and put my finger in the mark of the nails and my hand in his side." Centuries from now when the mystery of Jesus’ disappearance from the grave has been solved and named the Resurrection and has become the account in the Christian scriptures upon which our entire religion hinges, and the celebration of Easter has spread across the globe, Christians will still give you a bad rap for being hard hearted, dubbing you “Doubting Thomas”—although some interpreters will spread the blame a little and criticize the disciples for being such lackluster evangelists, that they couldn’t even convince one of their closest friends. In the far future, some will wonder why all of you kept hiding in a locked room after Mary shared her incredible news, not understanding that you all were frightened of the religious authorities, and the state, and distraught over Jesus’ death. You will want to tell them to think about their own lives, those moments of profound grief, or even joy, when change topples the old life, strips you raw, and you don’t know what comes next. You will want to remind them that though they might recognize something profound and life-altering is taking place when it happens, rarely do any of us understand the meaning of such events as they are happening. Meaning making emerges as we live into the hidden beyond of such moments and integrate this new reality into our daily existence. It takes time to develop perspective to understand the significance of events that have shaped our futures and illuminated our pasts. Thomas, your reaction is completely human. For you, the rising is still a rumor, but your response is a sign of faith. Wrestling with doubt is a sign of your desire to believe and for that belief to emerge from your own experience and understanding, not from hearsay, or by adopting the experience of your friends when it is not your own, but by finding something you can grasp onto that will bring your toward belief. It seems natural to ask for the same appearance and signs your friends received—the sight of Jesus and his wounds, his presence with you—because literally, while you were out of the room, the rules about everything changed. A week later, you are gathered with your friends in that same house, doors still locked, everyone still huddling together trying to figure out what comes next. For the second time, Jesus walks through closed doors and appears in this place, before his closest friends, including you this time. "Peace be with you,” Jesus says to everyone. Then he turns to you and speaks as though he’d heard what you said a week ago, "Put your finger here and see my hands. Reach out your hand and put it in my side. Do not doubt but believe." You take a breath and all your wrestling and doubt vanish. At the first sight of Jesus and at sound of his voice, you recognize your beloved master standing before you, his features familiar, though his body has defied time and space and death. He still bears the wounds of persecution, but you do not have to touch them or him to believe—though soon you will embrace. Your questioning has led to complete and utter faith. Here is Jesus no longer dead, but risen, capable of all things beyond your understanding, and you drop to your knees in a sweet flood of relief, surrender, and hope, uttering the words you now know to be true: “My Lord and my God!” You are the first person to name the significance of the Risen Lord, you are the first one, who after seeing Jesus resurrected, understands just what he has encountered, the one who can now help the other disciples interpret history in the making and encourage them into boldness of their own. To your declaration Jesus responds: "Have you believed because you have seen me? Blessed are those who have not seen and yet have come to believe." In the future, some might hear these words as a rebuke of you, implying that you should’ve believed the disciples when they first told you. But as John writes his gospel, his intent is not to use Jesus’ words to criticize you, but rather to offer hope to the early church that would form in the next decades, to record this sign and wonder, one of many they would not see in person, so that they might also believe. John didn’t know what the future would hold. Couldn’t know that the saving message of Christ would spread throughout a world much vaster than any of them had ever imagined. John couldn’t know that the Resurrection was the beginning of time as we mark it. Jesus’ blessing of those who believe without seeing doesn't negate those who believe because they see. Here in the year of our Lord two thousand nineteen, we have only to look at the journey of saints and mystics, religious leaders, and everyday believers across the centuries whose faith allows us to see Christ alive in the world. When we embrace the mystery of the risen Christ, when we follow Thomas’ example, then our fears, worries, questions, and grief can shift inside us and become the underpinnings of faith as we begin to trust in what once seemed impossible. In our un-doubting, comes our blessing: Blessed are we who live on the far side of the Resurrection. Blessed are we with centuries of the faithful traveling before us. Blessed are we who have been breathed on by the Holy Spirit. Blessed are we who are searching and questioning. Blessed are we, who like Thomas, who both see and believe. As we receive and respond to that blessing, may we become bearers of light, the embodiment of God’s love for others in this time and this place. May we, even in all our shortcomings become the hands and feet of Christ, our dear Savior whose horrific death was redeemed; whose rising has made all things new.

0 Comments

In the Empty Tomb

You who’ve put on new life You who wear Resurrection like a clean white robe scrub me to the bone then let me rest alongside you for just a moment—the two of us shiny, pink, expectant radiant in our empty tomb ...... The Resurrection What would Jesus give us If we asked Our hearts broken in three pieces With grave clothes entombed He has nothing left But a set of wings To resurrect our faith Holy Week It’s time to walk tenderly along the rutted road feet blistered bare and dusty trouble plodding doggedly at your heels When hope is all that remains and your palms are rope-burned red make of faith and doubt a lifeline, not a noose and grasp tight despite the pain Gather up grief and despair lay them in baskets woven from reed and tears then lay your woes before the one who will not stay entombed Build an altar caged by ribs for the one who animates your every breath from birth to death who soon (all too soon) will cradle you home What He Said After Dinner In a moment I am leaving you In a moment I am gone returning to the One from whom I have come It will be time for you to be lost without me Time for you to wander the landscape of your familiar only to find it utterly desolate completely foreign I can’t tell you how to manage how to create a life from ashes only to say that you will do it It is your nature to grasp the limb of hope hold fast against the river of events that will sweep me away When you arrive safe on the other shore you will wail gnash your teeth curse the one who made us After you have blamed yourself for what you did not do you will catch sight of me scratch your head and wonder convinced that you are mistaken that my return is impossible Listen to your heart leap with recognition believe In that moment the entire world will change Wrestling the Good from Friday

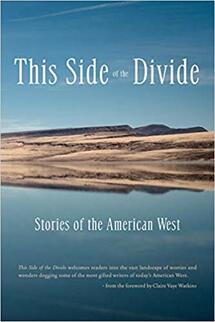

On this day of your suffering and crucifixion we on the far side of the resurrection remember more than we mourn— Our hope refuses to die but what of yours, Dear Teacher? Do you know hanging from your cross as the sun is eclipsed that you have not been forsaken that “It is finished” becomes a beginning? O Sweet Savior we weep for the many times we did not understand or believe the truths you tried to tell us. For us the tomb is always empty come Easter. Though we have failed you though we do not deserve it salvation arrives. We live through these bleak days because, finally, we believe in you. Now, we beg you just this once, to believe in us. Saturday night I had the pleasure of reading from my short story "Impressions of a Family" along with four other readers included in Baobab Press' new anthology This Side of the Divide: Contemporary Stories of the American West, produced with the assistance of MFA students at the University of Nevada, Reno. The event was held in Portland in conjunction with the AWP writing conference—14,000 writers gathered to take part in 550 official presentations, a massive book fair, and dozens offsite events, like the one I participated in at Mother Foucault's Bookshop. I was fortunate and delighted to have four good friends cheering me from the audience. For those of you who couldn't join us, here are the excerpts I read. You can order a copy of the anthology here. And yes, that's Van Gogh's "Starry Night" I'm wearing, and yes my skirt received its own round of applause! EXCERPTS:

My father is dying. He’s been dying all week. I know it when I see him opalescent and shrunken, bony in the nursing home bed. My stepmother Janice leaves her place at his arm, and I shuffle in, nudging my son Jared in front of me. It’s the first time Jared and I have been together since August when he moved in with his father, my ex-husband, to attend an arts high school. I lean alongside Jared’s shoulder, which tops mine now, and squeeze my father’s flaccid hand. I remember it firm and huge. “Hi, Dad.” His eyes flick in my direction. “I brought Jared to see you.” “Hi, Grandpa.” Jared inches closer and peers at his grandfather. The last time they met was almost a year and a half ago, after my father’s first stroke, and Jared was pissed that he missed his first day of high school to visit some stupid stranger, as he put it. My father lets go of my hand and reaches for Jared’s. “Straight on ’til morning,” he says, quoting Peter Pan, his voice hoarse. I see their interlocked palms—-pale and fading, strong and tan. The last time they held hands was also in a hospital. Jared’s newborn fingers, tiny pearls, curled around my father’s index finger, firm and golden. My father had driven the length of the state to meet his first-born grandchild, only to kiss us both, buy Jared a stuffed giraffe from the gift shop, then turn around and leave within twenty minutes. I can tell Jared thinks I’m the only link between them, the one who holds them together. But I feel the inverse, the force with which their lives have forged me. First, my father’s distance, cool as ice in a whiskey glass, even before he left, then Jared’s infant need that demanded all my time, all my attention, all my wonder, and then evaporated before I was ready. I rest my hand on theirs for just a moment before Jared wriggles from our grip. The next day Janice and I join my father at the convalescent home again. We make small talk and greet visitors. “Oh, you’re the teacher from Napa,” they say. “Isn’t your son the one who’s attending the high school for the arts? He wants to be a painter, right?” I’m invariably surprised they’ve heard of us. An attendant brings in lunch, solids exchanged for purees, and Janice feeds my father, though he seems barely conscious. “Just one more bite,” becomes her prayer, but he’s helpless as a newborn bird, and with each meal less able to prove his love for her. I flip through a magazine and try not to watch. That night after his ski trip, I lure Jared to the Best Western with the promise of all-you-can-eat pizza and in-room movies. When I pick him up Don’s new wife fills the doorframe with her big hair, big teeth, and big breasts. “You’re early, Jared’s in the shower.” Rhonda pauses. “Won’t you come in?” We’d both prefer that I wait outside, but it’s dark and sprinkling and that wouldn’t be civil, and we try to be the poster family for modern divorce. Jared takes the stairs two at a time. He’s carrying his portfolio on one shoulder. His wet curls glisten. After he’s eaten seven slices of pizza, and about eighty-seven people are killed in Jean-Claude Van Damme’s latest movie, I ask Jared how he likes living in L.A. Instead of answering directly, he spreads his portfolio over one of the beds. He’s done dozens of sketches and almost as many paintings this semester. He holds each piece, framing it with his delicate fingers. “There are five principles of organization,” he explains as if he’s giving a school report. “Balance, movement, contrast, emphasis, and harmony.” He has me compare a series of charcoal sketches, and we determine that I favor irregular rhythm, and asymmetrical over radial or formal balance. “You’re catching on, Mom. Now, there are five basic elements of design: line, shape, color, texture, and space.” I study watercolor, oil, and pastel renditions of the same still life until I can correctly identify realistic from abstract shape, dark from light values, actual from simulated texture, and positive versus negative space. He shows me an experiment in Pointillism. “Everything is made up of tiny dots using only primary and secondary colors. What do you think?” “It feels static.” I do my best to sound like an art critic and not a mother who wants to snatch her son back for purely selfish reasons. “Exactly. The precision of color sucks all the life out of it. That’s why I like Impressionism. This is my favorite.” He holds up a painting of our yard in Napa. From across the room I see everything clearly, the dilapidated barn, the almonds and magnolia in flower, chickens pecking near the pond. When I come close, the images blur and become indistinct. They could be anything. Jared falls asleep while I floss my teeth. He’s sprawled across the bedspread, face down. I pull a corner over him and rest a hand on his back, feeling the shallow rise and fall. When he was a baby, Jared couldn’t fall asleep without my hand on the round of his back. Until he was three, I eased him into his crib after our ritual rocking and countless verses of “Bye Bye Baby Bunting.” I stood for long minutes with my hand across his spine waiting for the breath of sleep. Gradually, I retracted my hand into the space above him, feeling the connection between us diminish. Finally, I’d turn to tiptoe away, but often he sensed me move, and I’d repeat the process again. I was everything he wanted, and everything I could give him was enough. But I wonder now if that was ever completely true. Because Don was there, too, often taking my place on the second and third rounds of hand-on-the-back sneak-away. My marriage is over, but Don did not evaporate from Jared’s life the way my father evaporated from mine. My son has a father whose love is visible and present. I lift my hand and crawl into my bed. Jared doesn’t move. In the morning Jared asks me to take him to the Rose Parade New Year’s Day. “It depends.” I park on the street. “I mean, if Grandpa doesn’t kick off tonight.” “That’s rude.” I open my door. “Sorry.” Jared shrugs. “But it’s also true.” Don is a landscape architect who specializes in ripping out lawns and flowerbeds and replacing them with gravel. He calls it xeriscape. This morning he is washing his truck with some eco product from a spray bottle and pretends not to see me while I walk to the front door with Jared’s portfolio while they talk. “Dad said okay.” “Great.” “I love you, Mom.” He hugs me. I hug too hard. He bounces into the house. I walk toward Don who looks up. “I’ll probably be over really early tomorrow,” I say. “I hope it won’t interfere with your New Year’s plans.” “It’s fine. It’ll be good for the two of you. Jared won’t say it, but he misses you.” I nod. “He seems happy here. I’m glad.” “I’m sorry about your dad.” “Thanks.” “I never liked him.” He smiles, quick and sad, a lapse in the usual reserve. “I know. Thank you for that.” I return the smile and remember the afternoon I told Don about my father. “What kind of scumbag runs out on his family?” he’d asked while we were twined in bed. “I will never leave my family. When I get married, it will last forever.” It was a proposal, a confession, and an opportunity for someone to hate my father for me. Jared is a kid who sticks to his New Year’s Resolutions. “What did you resolve, Mommy?” he used to ask, showing me his crayoned list. “Nothing.” I’d reply. No resolution, no failure. This year it’s different. Alone in my hotel room, I can’t sleep. There’s a party in the lobby, firecrackers in the street, and a new century ready to impact me. I take a sheet of stationery from the bedside table and write resolutions for the first time in ages.

I want to write something about coming to understand in a deep way the difference between being alone and being abandoned, but I can’t figure out how to phrase it. I fall asleep with pen in hand. |

I began blogging about "This or Something Better" in 2011 when my husband and I were discerning what came next in our lives, which turned out to be relocating to Puget Sound from our Native California. My older posts can be found here.

Categories

All

Archives

September 2023

Newsletters |