|

A message for the community of St. David of Wales, June 2022.

I used to love Pentecost and the images of fire, the tongues of flame hovering over the disciples’ heads. I wrote poetry about the hot breath of God on our faces, the spirit scorching our hair and singeing off our eyebrows and throwing us into the street chased by tongues of flame. Back then, I was a stay-at-home mom, a classroom volunteer, a Sunday school teacher with a tiny life and small circle of influence, who had just felt a call from God to write as a form of ministry. I found myself on fire for God in ways that burned up all my earlier doubts and fears about being the right kind of believer. And the idea of Pentecost coming to set us on fire, to clean us to bone and sinew, felt absolutely right as I opened myself up to new bold ways of being in the world. That was more than twenty years ago, when the worst thing I could imagine happening to my children in their classrooms was contracting head lice, not being fired upon. That was decades before COVID trapped us all in our own houses for months, long before I understood systemic racism and my privilege as a white woman.

0 Comments

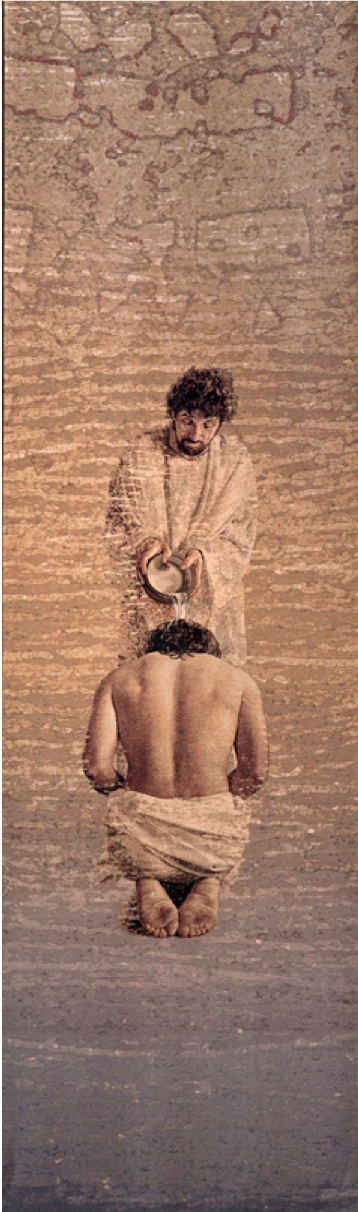

A reflection on Matthew 3:13-17 in observance of The Baptism of Our Lord. Thanks to St. David of Wales for the opportunity to deliver the message yesterday. Jesus was thirty years old when took the plunge. As scripture relates, he sought out his cousin, John, the desert dweller who ate locusts and honey and preached to a good-sized crowd to repent of their sins before he dunked the converts underwater. Matthew’s gospel tells us that John would have prevented Jesus’ baptism, saying, “I need to be baptized by you, and do you come to me?” But that Jesus answered him, “Let it be so now; for it is proper for us in this way to fulfill all righteousness.” It seems an odd statement from Jesus, who doesn’t come across as a man concerned by what is proper. In fact, he’s usually the opposite, setting aside customs and rules that interfere with right relationships. Did propriety really compel Jesus to show up at the river? Or was it something else? There are no Biblical clues. We assume that Jesus already knew his identity as Son of Man, that he was aware he’d been born to a unique destiny, that showing up at the riverbank and submitting to John’s baptism was perhaps a formality, the ceremonial swearing in after God’s election. And soon after his baptism he finds himself on a vision quest in the wilderness battling temptations as he determines how to live out his destiny. But on the day of his baptism Jesus queued up along the riverbank with the other sinners, with nothing in his appearance or reputation signifying to anyone that he was anything other than exactly like them. A person, soon to be wet and repentant, sharing a desire to turn their lives around, or at least to align them more closely with what they perceived in John’s message to be God’s intentions. Whatever private message God had telegraphed to Jesus over the previous thirty years when he sat by firelight sharpening his carpentry tools and contemplating life was confirmed in the light of day along the banks of the Jordan, in front of the crowd, who must have been startled by the resulting thunderclaps, the holy spirit descending as a dove from the clouds, and the booming voice of God announcing his Son’s belovedness. Baptism of water and the Holy Spirit was the first sacrament that Jesus instituted among his followers; the Eucharist was the second. Two thousand years later, public baptism remains the principal Christian rite for those who want to join with Jesus. I assume that most, if not all of us, in this room have been baptized. And most of us have stories about that momentous event the Book of Common Prayer defines as “union with Christ in his death, resurrection, birth into God’s family the Church, forgiveness of sins, and new life in the Holy Spirit” (p. 858). I was twenty-four when I was baptized in 1985, standing in front of a United Methodist congregation of sixty or so people as my pastor dipped his hand into a small bowl of water and touched it to my forehead three times. In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit, he baptized—my bangs. Water never touched my skin. I had thought of baptism as a sin-proof coating like Teflon. Promise to stop doing things my grandmother (the only religious person in my family) would disapprove of, apply water to skin, and after death I wouldn’t burn to a crackly crisp in hell-fire. The words in the United Methodist Hymnal were pretty clear, “Forasmuch as all have sinned and fallen short of the glory of God, our Savior Christ said, ‘Unless one is born of water and the Spirit, one cannot enter the kingdom of heaven.’” It was one thing not to have been baptized when I didn’t believe in God. But, once I was a believer, wasn’t I still in danger of the fiery pit since I hadn’t been adequately spritzed? Sister Ishpriya wrote, “a tiny drop of water can cleanse the whole of my impurity when blessed by your forgiveness. But, O Lord, more than all this, this tiny bit of water passed over my head is the symbol of my birth in You.” A tiny drop of water on my face—Was it too much to ask? “The Baptismal Covenant is God’s word to us, proclaiming our adoption by grace, and our word to God, promising our response of faith and love,” the United Methodist Book of Worship told me. I had done my part with my vows, but I was convinced my pastor had failed in carrying out God’s part and suspected my baptism was a fake, though I’d later learn that Methodists, like Episcopalians, believe that baptism is “permanent and indelible” (Walk in Love p. 25). I smiled when people hugged me after the service, but deep down I worried that I was still flammable. I knew I was God’s, but not because of this ceremony, where there certainly hadn’t been enough water to scrub even a follicle of me clean from sin, but because God had come into my life a few months earlier and arrived while I was in the shower. As I rinsed off the last suds of soap, the water changed. It flowed softer, filling me from inside out with what I can only describe as pure love. This love wasn’t a zingy, romantic pulsing, it was absolute and unconditional, love I’d later feel for my daughters at birth. This love was expansive, excessive, a gift I hadn’t even known I’d asked for. I had no doubt this love came from God, and later, when I came to know the stories, it seemed entirely plausible. If Jesus could turn barrels of water into wine at a wedding reception to please his earthly mother, then his unearthly father could change water to love in my bathroom pipes. When I turned off the faucet and reached for a towel, I felt like a different person, raw and alive, claimed. God loved me and I had to respond. I’d overheard something about leaving everything to follow Jesus. Was I supposed to leave my husband and join a convent, or move to a kibbutz? I decided to attend a peace study at the local United Methodist Church instead. I took a membership class after that appreciated a faith that took into account not simply scripture, but tradition, experience, and reason. I was encouraged to think for myself, something I’d always assumed becoming a Christian would negate. The social principles focused on everything from eradicating poverty and disease, to fair wages and union rights, from racial equality and respect for the environment to opposition to gambling. This care for others was so broad and contrary to the cries I’d heard from Bible thumpers during my college years, and so close to the values I held, that I was prepared to pledge my prayers, presence, gifts and service. The only obstacle to my membership was fact I hadn’t been baptized. It was an easy problem to solve. I didn’t need a class to study biblical accounts and precedents or understand historical or theological reasons for baptism. I only needed a few more questions inserted before my membership vows. My pastor didn’t even tell me specifically how my baptism would be done. If he had, I might have reached up and pushed my bangs to one side. If I’d had access to the Book of Worship then, I would’ve read, United Methodists, like Episcopalians, “may baptize by any of the modes used by Christians. Candidates…have the choice of sprinkling, pouring, or immersion; and pastors and congregations should be prepared to honor requests for baptism in any of these modes.” Knowing that, what mode would I have chosen that might have felt as powerful as my shower experience? By the time my oldest daughter was born in 1988, I’d come to understand that baptism was more about the type of claiming that brought doves to Jesus and unconditional love to my shower––a recognition that we belonged to God—and less about applying two molecules of hydrogen and one of oxygen to human skin as insurance. But I wanted her welcomed into the arms and family of God from the very beginning of her life something so absent in mine, so she was baptized at six months old, though I answered on her before. Like before, I repented of sin and declared Jesus Christ as my Savior. But this time, I pledged to nurture my daughter in Christ’s holy church and was aware of the congregation’s pledge to do the same. The pastor dribbled water on my baby’s mercifully bald head. Jennifer’s scalp wasn’t soaked, but there was no doubt she felt something. Her eyes grew wide. She looked straight at Pastor Lorraine who took Jennifer in her arms, lifted her high overhead and walked down the aisles presenting the newest daughter in Christ. Even now I think sprinkling seems the perfect way to baptize a baby, the water splashing like tears of joy, as we become aware of how precious life is, and how this ritual is not only an offer by flawed human beings to raise a child to know God, but acknowledgment that this young life is as pure and full of possibility and unconditional love as it ever will be. The infant baptism of sprinkling wraps water and spirit and gratitude and enormity into a holy moment filled with unseen and ever present doves and voices. We know the beloved is in our midst, in the form of this tiny person. But sprinkling for me as an adult was a complete bust. I was a Southern California water baby. The first fourteen years of my life if I wasn’t swimming in the community pool, wading and bodysurfing along the shore, or submerged in the bathtub submerged, I was drying off. What type of baptism would feel most like giving up an old life and becoming a new creature? It was more than decade after my baptism that I first saw pouring. Thirty-year-old Shannon, with a purple beach towel wrapped around her neck, received a pitcher of water overhead as she knelt before the altar. The towel took the brunt of the water, but the back of her gauzy dress darkened, and she sat in clammy garments during the remainder of the worship service. I was baptized in November, and even in retrospect, the idea of a quart of water dumped over my head in the midst of a Sunday service on a cold cloudy morning wasn’t appealing. Under the right circumstances, though, pouring does have its appeal. In the Cathedral of our Lady of Angels in Los Angeles, California, “The Baptism of the Lord” is depicted in the center panel of the baptistery tapestries designed and woven by John Nava. This is the image on our bulletin cover today. Against a background of sand that wavers like a mirage, Jesus kneels low, bare backed, head bowed before John. His legs are not immersed in the watery Jordan, but pressed against its gritty bank. John, looking tenderly at his cousin’s submission, pours a bowl of water over Jesus’ head.

The gentle cascade saturates his hair, cools his scalp, refreshes him in the scorching heat. Jesus can feel the small stream of water, each drop sliding over his skin, and in John’s measured pouring he has time to breathe deeply of the significance of this moment. Soon the heavens will open, soon the voice that called us into being will speak to the crowds, and will say of this son, the words we all long to hear, “You are my beloved.” Finally, there is immersion. As much as I’d like to think I’d have chosen immersion, the truth is, even if I’d known it was possible, standing on the banks of the local reservoir while my pastor dunked me into the municipal water supply would’ve been too much spectacle as a fledgling believer. But many years later, I stood with my congregation on a hot Sunday morning as we concluded worship at the edge of a swimming pool to witness ten-year-old Sarah’s baptism. Over their bathing suits, she and our pastor wore white robes that billowed around them as they waded in. Secure in Pastor Margo’s arms, Sara went under, and reemerged soaking, hair plastered to head, watered to the bone. Then, as she climbed out of the pool, water flowing from her robe, we gingerly hugged Sara, trying not to get too wet. “Baptism is both God’s act of grace in the world and the human community’s response to that grace in faith and obedience,” according to the Book of Worship, and Sara’s was close to the way I imagined the experience of those who came to John the Baptist, as they flooded to the Jordan River, eager for sin cleansing and a fresh start. They kicked off their sandals and waded in, gasping a bit when the water slapped against their hips and stomachs. Then they held their breath as John dunked them under. There was the sensation of surrender, closing their eyes, allowing themselves to be submerged, the shock of cool water enveloping them, the smallest sensation of drowning before they surfaced gasping, and stumbled ashore into the arms of family, friends, and even strangers afterward. Before Jesus came on the scene, John warned them that there was more to it, that this was just the beginning. Someone else was coming who was going to baptize with fire. No doubt that branding would sear us into family, scar us for life, leaving marks no one could ignore or forget. Whether the people listened, whether they followed Jesus into the fire or not, there could be no arguing that their baptisms were memorable. In the Methodist tradition, each year on this Sunday when we celebrate the Baptism of the Lord, and each time there is a baptism, we are called to “Remember your Baptism and be thankful.” It wasn’t hard for me to remember mine, but I couldn’t bring myself to be thankful. When I didn’t want to remember my shoddy baptism, I remembered both my daughters’ baptisms, and how meaningful they were to me, though my children have no memory of their baptisms outside photos and stories I’ve given them, and I wonder if I have taken from them the opportunity to remember and be thankful. I’m too new to the Episcopal Church to have experienced many of the traditions that surround this day. But I do know that, as much as we try, we can never do God right. Our sacraments and rituals, the big moments in our lives of faith will always reflect our humanity, our frailties, bad aim, and the things our parents did or didn’t choose for us. My baptism wasn’t the big bang I longed for. But as I look back, I can see the event perfectly illustrated not only my need for God’s grace, but my need to extend grace to my pastor, to the congregation, to God and even to myself. As Gayle Felton writes in This Gift of Water, “Baptism, then, is not so much an event as it is a process…dynamic, not static; a journey, not a destination; a quest, not an acquisition.” Today we come to the water alongside Jesus, who had no need for repentance, but who chose to be baptized, his first step into the river of his destiny. He chose to enter into our human experience entirely, despite his divinity. He became one of us and through his surrender, he was filled with the Holy Spirit, the comforter he would leave with us. With him we step into the river, we submerge under water that envelops us like our first home where we are cradled and blessed before birth, a place we can only occupy momentarily as we hold our breath and float in the weightless present that surrounds us in the expansive love of our Creator, dying to all that would separate us from that love. And when we can bear it no longer, we emerge from the water gasping, blinking, dripping, shivering, filled with the reminder of who we are and whose we are. May, each dip into river, Sound, lake, and stream, may each flume of sea spray, each drop of rain upon our skin, each sprinkling of the shower head and garden hose, each submersion into bath and dishwater, each hand dipped into the baptismal font before worship remind us again and again that we are God’s beloved. And to paraphrase the Book of Common Prayer, may that belovedness raise us to a new life of grace, give us an inquiring and discerning hearts, the courage and will to persevere, and the gift of joy and wonder in all God’s works. Amen. (p. 308) A Reflection on Luke 15:1-10

Back in the summer of 1974, when I’d just turned thirteen, I attended my first major league baseball game at Angel Stadium in Anaheim not too far from our home. My mom, my stepdad, and I met up with another couple and their eight-year-old daughter, whom I often babysat. I can’t tell you who the Angels were playing that night, or if Nolan Ryan pitched one of his no-hitters, but I can tell you that even as a Southern California kid who’d been to Disneyland at least a dozen times, I’d never seen so many people in one place at one time. Stadium capacity at the time was 43,000, and I have no idea how many people were in the stands, only that when the game was over, we all poured out of the bleachers heading down corridors elbow-to-elbow swarming toward the exit as if we were a school of tightly packed grunion headed toward the beach. I shuffled out behind my parents’ friends and their daughter, trying not to step on her small tennis-shoed feet. I remember chatting, but not about what, as we wound our way past closed concession stands and through the concourse. As we converged with another river of people approaching the exit, I realized I ought to be with my parents, not with their friends, since we were going home, and not to their house. I stopped walking, turned around, and was engulfed by a crowd of people streaming past me, none of whom were my parents. I scanned the faces coming toward me for a few seconds, and when I still didn’t see my mom and stepdad, I turned back around to resume walking with their friends—but they were gone. I stumbled into the crowd looking in vain for a familiar face as everyone pressed on toward the exit, taking me along with them. As I got closer to the wall of doors, I fully expected to see my parents and their friends standing just inside or outside the doors, waiting for me to join them. But they weren’t. Since I was a kid, used to reading in the backseat on car rides and usually oblivious to directions, I had no idea where my stepdad had parked his car or how I’d ever be able to find it and my parents. Panic and tears both began to rise as I realized I was truly lost. I guess my distress must’ve showed because soon a woman was standing in front of me asking if everything was okay. I told her I’d lost my parents. Not far away, she spotted a man in an official jacket—an usher or a security guard; I don’t remember which now—ushered me toward him and told him my predicament. She left when he took over, asking me to wait against a wall while he spoke into his walkie-talkie. Soon someone else in a uniform jacket appeared with a walkie-talkie clipped to his belt and I followed him through a door, down a flight of stairs to an underground level, and from there, down a long windowless corridor. He stopped and opened a door revealing half a dozen little kids, all lost like me, kept watch over by yet another uniformed adult. The person on watch explained that there were too many people outside right then to go looking for our parents. We would wait until the stadium emptied out and then they’d take us to find our parents. So, I sat on a bench, like the other kids and waited in silence, trying not to cry. Though I was relieved to be safe, I was also embarrassed. In any other circumstance, I’d be babysitting these kids, reading them bedtime stories and tucking them in and watching TV in their living rooms until their parents came home from the ballgame. I was at least twice their age, and almost five feet tall. I could see faces in the crowd when I’d been looking for my parents. These kids were probably staring at belts and waistbands; no wonder they’d gotten separated from their parents. What excuse did I have? None. I should’ve known better than to get lost. I felt stupid, thoroughly humiliated, and convinced my error was going to put me in so much trouble once I was finally reunited with my parents. The minutes dragged on until finally our supervisor opened the door and ushered us onto a waiting motorized cart with bench seats. The driver cruised through the building and out toward the parking lot, which ringed the entire arena. He told us not to worry, that he’d approach each lingering vehicle, and eventually we’d all find our parents. “Believe me,” he said, “they’re waiting for you.” As we turned into the first parking area, there were still dozens of cars in the lot, many more cars than lost children, but I could see that some vehicles had their emergency flashers on, headlights blinking in the dark summer night, beckoning us. I don’t remember where I was in the lineup of reunification, but I do remember the driver commenting on how helpful the flashing headlights were when he pulled up next to my stepdad’s car. The driver said parents didn’t usually think to do that, and my stepdad responded that he’d circled the entire parking lot looking for me, and as he stopped to talk to other parents of lost kids, he’d told each of them to turn on their flashers. As the driver and my stepdad thanked each other, I stepped down from the electric cart and into my mother’s warm embrace. Then, as the cart continued on its mission, I climbed into the backseat, waiting for the dreaded reprimand, surprised that it never came. All these years later, I’m still anxious about being separated in large crowds. Every time I leave an arena, my experience at Angel Stadium surfaces, and I hold tight to the hand of whoever I’m with, afraid I’ll get lost again. Encountering this scripture passage brought the incident and my anxiety to the foreground of my thoughts. And for that, I find myself unexpectedly grateful. The process of immersing myself in Luke’s words allowed me to see the situation from other perspectives, not only as the sheep or coin or young teenager who was lost, but as the shepherd and the woman who cleaned her house, and the kind woman, security team, and stepdad who all helped in the search to find that which was lost. It’s likely that you, like me, have been lost in a situation that still sticks with you many years later. Maybe it happened while visiting a new place, or driving with bad directions, or out on a hike. Or maybe it was less of a geographical situation and more of an emotional one—feeling lost and unmoored after an unexpected move, or unsure of what comes next after the children left home, or after the death of a loved one. Whatever the particulars, each of us in our own lives and in our own ways has been lost—to ourselves, or to those we love, or to our faith in God. And perhaps you, like me, have approached being lost with judgment about yourself, with feelings of failure or inadequacy that lingered long after you were found or found yourself. Reading Jesus’ parables about the lost sheep and lost coin, and applying them to my own life, I find good news for those of us who are lost: First: There are people looking for us, even when we don’t about it and can’t see them. The shepherd leaves his flock—hopefully in a safe place—to search for the lost one. The woman tears her house apart, cleaning from top to bottom to find the coin. I don’t know when my parents realized I wasn’t with them, and even though they weren’t where I hoped or expected them to be, they were out looking for me, sending out SOS signals with flashing headlights, even helping others to find their lost children. Second: Things and people get lost. Getting lost isn’t an intellectual, moral, or spiritual failure. It’s reality, and when people see that reality, they respond. The shepherd retraces the paths he’s led the sheep on, the woman sweeps and looks in every place her coins could possibly be, strangers see lost children and young teens and offer help, the baseball stadium staff have protocols to reunite lost children with parents, parents turn on flashing beacons. None of them just sit there saying, “Oh well, it’s lost,” or, “Oh, well, she’s lost. There’s nothing we can do about it,” or “It’s her own fault she got lost, let her find herself by herself,” or “Oh well, I didn’t need that sheep, or coin, or kid anyway,” or “Oh well, I’ll get a new sheep, a new coin, a new child.” When we who are lost feel powerless to change our circumstances, there are people and forces greater than ourselves working on our behalf. Help is available in our distress, even if we don’t know how to ask for it, and even if we don’t recognize our need. And perhaps most importantly, especially for those of us who are prone to punishing ourselves for making mistakes: Joy is the proper response once we’re found, no matter what circumstances led to our being lost. The shepherd didn’t banish the wayward sheep for wandering away. The woman didn’t give away all her coins; she didn’t decide that in losing one coin she was too careless to be responsible for any coins. The stranger who asked if I was okay didn’t say that it was ridiculous for a teen to get lost in the crowd. The security staff didn’t lecture us kids to be more careful or responsible while they waited to return us to our parents. My parents didn’t shame or scold or punish me once I was found. They shared some responsibility, wishing they’d been more attentive and hadn’t lost track of me. But they didn’t wallow in self-recrimination and decide we could never go anywhere again because we might get separated. The shepherd, the woman with her coins, my parents: they all were happy to have that which was lost restored to them. Each celebrated. In the gospel, the shepherd and the woman invited their friends and neighbors and threw a party. My parents hugged me. I’d like to say that we went out for ice cream with their friends who’d waited to see that I was returned safely; but I don’t remember if the friends stayed or what happened next. What I do know is that in our finding, we are recipients of grace, of unconditional love, of welcome and celebration. A point that Jesus makes abundantly clear to those who are judging him about the company he keeps. He reminds the righteous that the welfare of each person, whether we “approve” of them or not, is important to all of us. And he asks us to consider the impact in our own lives when we have lost something or someone important to us. “Suppose one of you has a hundred sheep and loses one of them,” Jesus says. He doesn’t ask us to suppose we are the sheep or the coin, but that’s often our first instinct. What is our modern day sheep? A missing pet? A family member struggling with addiction? A friend suffering from depression? A child caught in a custody battle between acrimonious parents? A fellow parishioner who has stopped coming to worship? What is our modern day coin? A wedding ring? A family heirloom? A vehicle registration? Who are our modern day sinners and tax collectors? Telemarketers? Internet scammers? Sex Workers? Drug dealers? People in the political party we’re not? Whatever form the sheep or coin takes for us, whoever the sinners and tax collectors are, Jesus calls us to seek that which has been lost to us, to include those who have been excluded—and further calls us to rejoice at the reunification. Celebration sounds wonderful, but can be so difficult when what or who we’ve lost has hurt us. Words that wound our pride. Spouses who break our hearts. Addictions that poison relationships. Bosses who fire us. Churches that drill in sinfulness to the exclusion of grace. And Sons who beg for their inheritance early and run away to squander it—as happens in the next verses of Luke’s gospel. It’s difficult when these lost things are restored to believe that they’ll remain found. It’s hard to welcome them wholeheartedly and take the risk of losing them again and being hurt again and not having life work out the way we want. It seems safer to be wary, to require assurances through scripted behaviors, specific beliefs, court orders, drug tests, or some other external proof that the restoration is real, that promises will be kept, that things will be different this time around. But if God doesn’t require us to swear oaths and sign promises in order to welcome us into relationship, if God doesn’t need anything more than us as we are to celebrate our belonging and love us unconditionally, then our rules about belonging simply don’t hold up. Most of those who judged Jesus genuinely believed their reasons for exclusion were justified. His ideas were so radical, his words and actions threatened their religious practices and their very identities. For us, Jesus words may be simple to embrace, but living them out is much more difficult. Be like the shepherd who seeks the lost sheep until it’s found. Be like the woman who cleans her house until she recovers her lost coin. Be like the father welcomes the prodigal son with no questions asked. Be generous; Be merciful. May Jesus’ words open our eyes, our minds, and our hearts. May his words remind us that to be human is to be lost to be human is to be found, to be human is to seek, to be human is to find to be human is to forgive others and ourselves, to be human is to celebrate inclusion to be human is to live and love in the manner of the one who gave his life in love for us. A slightly modified version of my most recent sermon based on Luke 13:10-17, the healing of the bent over woman.

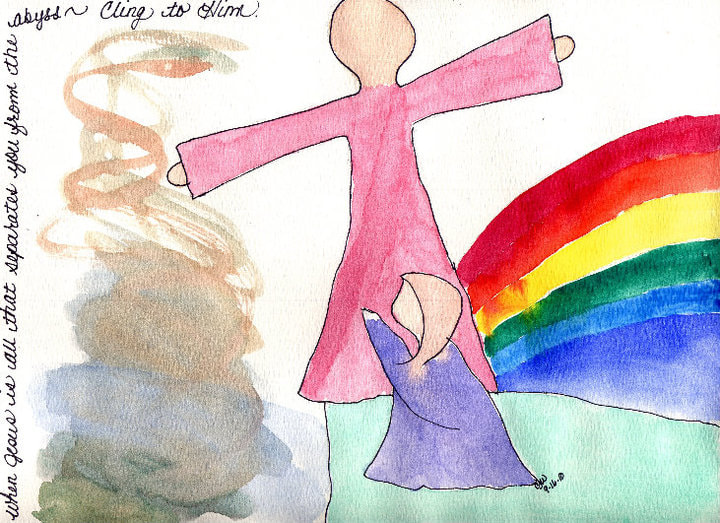

There is so much richness in this relatively short scripture passage, so many themes we could explore about the nature of the Sabbath, about our human tendency to put rules and regulations around our humanity, about Jesus’ ministry and his words and actions that illuminate the differences between the spirit of the law and the letter of it, so that we might learn to choose the law of love above any other. But it is the bent over woman herself who draws me most deeply into this gospel reading and sparks my curiosity: Who is this bent over woman? How old is she? Is she married, widowed? Who is she living with? What is her role in the household and community? What happened to her body, and how did her physical ailment impact her spirit with each passing year? Given the time period, did her family and community think her condition was a result of her sin? Did they care for her, or ostracize her, or perhaps both? Did she fight against her body’s limitations in the beginning? Did she injure herself more by refusing to admit to her limitations? If she’d fought against this new reality, when did she stop fighting? And what sort of “giving up” was it? Resignation or acceptance? Had anyone tried to help her? Had she sought out cures? Did she come to the synagogue faithfully, or did she come that day just to see Jesus? Had she planned to ask him for healing? How had he noticed her? Why had he chosen to heal her and not someone else? What happened to the woman after the commotion of her healing died down? How did the people in her life and synagogue treat her after her healing? How did her daily life change? Was it Jesus’ words or his touch, or both that brought about her healing? In what ways did the healing of her body return her to her former life? And in what ways did it close her off to her former life yet open up to a new one? In what ways did this healing impact her body, mind and spirit? Does healing have to come in one dramatic moment, or can it be gradual? Most of my questions can’t be answered. But I want to understand the story of the woman in Luke’s gospel and learn about healing from it because I have both been a bent over woman myself, and I love and have cared for a bent over woman. The bent over woman I love and have cared for has been bound by physical, emotional, and spiritual pain for decades, a crippling that wouldn’t be a stretch to attribute to Satan, as does Jesus in this gospel. The experience of being in relationship with her has impacted me deeply. I have seen the loss of physical abilities and the insufficiency of treatment or cures. I’ve seen a person stripped of dignity, trapped in dependency, robbed of happiness, and beset by hopelessness and despair. There are moments, despite my love for her, and despite my own faith, when I do not think I can bear another moment of her suffering. I want Jesus to heal my bent over woman. I want him to say as he did to the daughter of Abraham: “Woman, you are set free from your ailment.” And I want him to do it now—or to have done it already, years ago. Each of us has been bent low in some way, crippled by illness or disease, by infirmity or job loss or natural disaster or divorce or grief or violence or any number of human experiences that derail our plans and identities. And our healing, and how, or when, or if it comes in this lifetime, can be unexpected and mysterious. I became a literal bent over woman in January 2016. I was crawling under bushes to dig out Himalayan blackberries by the roots when I felt a sharp twinge in my back. I hobbled into the house for a dose of ibuprofen and ice, but within a few days I couldn’t put weight on my right leg without crumpling. My husband drove me to Urgent Care that evening, and to the ER the next as the pain got worse. I was given a shot, prescription anti-inflammatory, painkillers, muscle relaxer, a pair of crutches, and told to rest. I spent weeks mostly laying on one side in a near-fetal position, unable move freely. Pain made me tired, grumpy, weepy, and narrowed my world. Sometimes my consciousness extended no further than my body as I sought a pain-free breath. I was completely dependent on my husband for dressing, bathing, meals, transportation, shopping, laundry, and housework. Though I was grateful for his uncomplaining generosity, it humbled me not to be able to contribute to our household, and to accept so much help. A month after the injury, I felt worse and not better. My doctor thought the initial diagnosis of a sprained iliac ligament and inflamed sciatic nerve, might be a herniated lumbar disk, and recommended an MRI, which my insurance wouldn’t pay for, saying I hadn’t suffered long or severely enough. I certainly felt I’d suffered long and severely enough so my husband and I, who were strapped for cash at the time, decided to charge the MRI to our credit card. I shared a prayer request on Facebook with my family and friends, and within an hour of scheduling the appointment, a loved one called and offered to pay for the procedure, though I hadn’t asked. I hadn’t recognized until that moment that there had already been some gifts in my suffering: In pain and illness, the trivial and irrelevant had been stripped away. Though I spent much of each day zoning out watching HGTV, I also appreciated daily life with a heightened awareness and gratitude: the beauty of sunrise and sunset, the melody rain on the roof, the many ways my body had so often done what I asked without protest. Accepting that I couldn’t cook or clean or even wash my hair and being vulnerable enough to ask for and receive help was part of my healing. As was accepting money for the MRI. It was gift I couldn’t repay. A gift given in love by someone who wanted to relieve my suffering and couldn’t; but could do this. I’d never had an MRI before, and I didn’t know I was claustrophobic until I was confined in that coffinlike tube with magnets banging like a jet turbine rattling my teeth and nerves. To quell panic, I brought hymns to mind, but my favorites, like “Morning Has Broken,” and “All Things Bright and Beautiful” were too happy for the circumstances. It was early February and Lent. I needed a hymn of lament and “O Sacred Head Now Wounded,” floated into consciousness where I repeated the lyrics in my mind like a mantra. I latched onto Jesus and the words of his wounding, for who and what else could be present with me there? Not the technician who was only a disembodied voice speaking via microphone between scans. Not my husband in the waiting room. Not even my wedding ring stashed in a locker with my clothes. In the middle of that MRI, clinging to Jesus, I knew that I would be healed no matter what images the machine generated, no matter what sort of treatment I would or wouldn’t receive. I knew because people I love had suffered much worse, and were whole despite diagnosis, disease, disability. God did not take the cup from them or from Jesus—though each asked to be spared. I can’t say if my doctor saw Jesus lurking between vertebrae when she read the MRI report, but I felt him—and the knowledge that God will not forsake us penetrated me bone deep. There was nothing more to resist. Somehow, in that blaring machine I was cradled and blessed. Feeling that blessing, I wondered if anyone had blessed the machine and the room, the technicians, physicians, and janitors who worked here, those who came here like me, under extreme circumstances, and our friends and families, at home, in the lobby, waiting, hoping, fearing, and I cobbled a silent prayer in the final minutes: “May this machine be used for the highest and best good by all who come in contact with it. May those entrusted to operate this equipment do so with great skill and compassion. May all who enter here be comforted.” Jesus spoke healing to the bent over daughter of Abraham, laid hands on her, and she stood up straight for the first time in eighteen years praising him. Two thousand years later on the far side of the resurrection, as I was bent over in pain, he healed me, and I praise him. Will Jesus heal the bent over woman I love and so many in our midst who are bound by illness, injury, addiction, trauma, abuse, who are crippled under the weight of so much they cannot bear to carry? I do not know, but I believe he is able and willing to heal us and waiting for us to come near, like the woman in scripture. I believe Jesus waits for us to surrender whatever it is that we cling to that stands between us and him. For some, like the bent over woman who suffered for eighteen years, that thing might well be her pain. If your pain is all that defines you, the only thing that has remained with you when everything and everyone else has deserted you, who are you without it? How can you possibly let it go and live when you have no idea what will happen? Where can you find that courage? Where do any of us find the courage when we’re bent low? Perhaps in the words of scripture. Perhaps through prayer. Perhaps by opening our eyes and our hearts and listening deeply to the experience of others who have found their way to healing. Perhaps all of these can lead us to take the first steps toward healing. I have been part of a faith community for the past year, lifting each other up in prayer every Sunday as we worship, kneeling at the altar together as we feed on the bread of life. I look at the faces of those who have become dear, and I know they know what it is to be bent over. And I know they know what it is to be healed. Among us, we know what it is to draw near Jesus and to surrender what we can’t control. I see faith in the midst of pain and suffering. I see wholeness and healing. I hear praise as we lift our voices in song. In a world where so much seems broken, where so many strive after a false illusion of happiness, where so many are bent over, I hear the hurting clamoring for reason to hope, looking for something to believe in. The daughter of Abraham Jesus set free immediately stood up and praised God, and I want to think that she told her story again and again over the years, to anyone who hadn’t heard it, and to those who had, but needed a reminder of God’s healing power. I want to imagine that she became a disciple in her own place in her own way. May we be like the daughter of Abraham. May we stand and speak. May we be emboldened to offer a glimmer of hope to those who are hurting, sharing not doctrine or theology, but the truth of our lives, the stories of our own pain and suffering, and the ways in which we risked opening ourselves to God’s presence to be healed by an outpouring of grace and love.  On the last Sunday of June, I stood in the backyard of a Victorian house in Loveland, Colorado, surrounded by 85 smiling, tearing with joy, happy people all dressed up and gathered to celebrate the wedding of two kind, smart, funny, and generous humans incredibly dear to us—one of them being my oldest daughter. I’d convinced myself, as the bride’s mother, that I’d cried all my tears several days before the ceremony when I wrote letters to my daughter and her betrothed. And, walking her down the aisle with my husband, the three of us were all smiles. My smile at moments looked more like a grimace, the eyes-screwed-shot-nearly-maniacal grin of the insanely happy, caught on camera. Everyone laughed at the best man’s speech; and the maid-of-honor, who’s been my daughter’s best friend since the age of three, gave a delightfully funny and sweet toast. Everyone guffawed when my husband, who used to work in high tech, rose and joked about not being able to use PowerPoint—a platform our daughter and her friends employed in high school to bolster their request to make an unchaperoned road trip—and became weepy when he spoke of his mother, who met the groom once when he and my daughter had first started dating, and had predicted their wedding long before they made that decision—as she had with my husband and me. The time came to read the poem I’d written, a blessing for two precious people, and emotion wracked my voice. This moment, this leap of love this saying yes spills from the lips of our beloved bride and groom words shimmering with joy. Together we celebrate the wonder of life in which these two so precious to each of us have found and chosen each other and today have pledged their lives to one another’s keeping. What a gift it is to journey alongside them in a world made sweeter by the kindness and generosity of their love. Cherished ones, may your marriage continue to bring out the best in each of you and each person blessed to know you now and in the years to come. After dinner, I’d learn that I’d made some of the bridesmaids “ugly cry.” Three of the “mom friends” in attendance, who’ve known my daughter almost as long as I have, were brought to tears as well. One couldn’t finish her meal. I know it wasn’t that my words were so exceptional or powerful, it was because love was overflowing, spilling out of us on this “happy, happy day,” to quote one of my daughter’s childhood friends. But on this happy, happy day there was still recognition of our human frailty: photos of the grandparents who’d died were on display next to the guestbook. And at 5,000 feet altitude some guests faced challenges: one with cancer suffered from the lack of oxygen, and even some who were healthy had headaches and trouble breathing, but they were all there; they’d come to celebrate love. One of the young bridesmaids was widowed less than a year ago, and despite her grief she hasn’t lost her riotous sense of humor as her infectious laugh rang throughout the weekend. I’m sure there were quiet moments that brought back bittersweet memories and sadness. I also know, that surrounded by her closest friends, she could be herself exactly as she needed to be in that moment. It wasn’t only the love of the bride and groom for each other that drew the wedding guests together and made the day so rich; it’s the love and care that this bride and groom have for their friends—the way they keep strong relationships over the years, the way they make new friends wherever they go, the generosity and kindness shown to others. We celebrated in a spirit of joy and abundance, and in those days of travel and celebration, I took a break from “the news of this world,” returning to it heartsick over all the ways we separate ourselves from love as a society. Outside of our circle of family and friends, we’re often fearful of others. We treat them in ways we’d never treat those we love, or those we just met at a wedding reception, or sadly even our unruly pets.

I want to hope that the gifts gleaned from my daughter’s wedding overflow into my behavior in the world: that I might see each person as a bride or bridesmaid, groom or groomsman, or the family, friends, parents, and children who love them and extend hospitality. And I want to hope that my small bit of generosity and kindness combined with your small bit of generosity and kindness can make a difference in the life of others—strangers and friends alike. |

I began blogging about "This or Something Better" in 2011 when my husband and I were discerning what came next in our lives, which turned out to be relocating to Puget Sound from our Native California. My older posts can be found here.

Categories

All

Archives

September 2023

Newsletters |