|

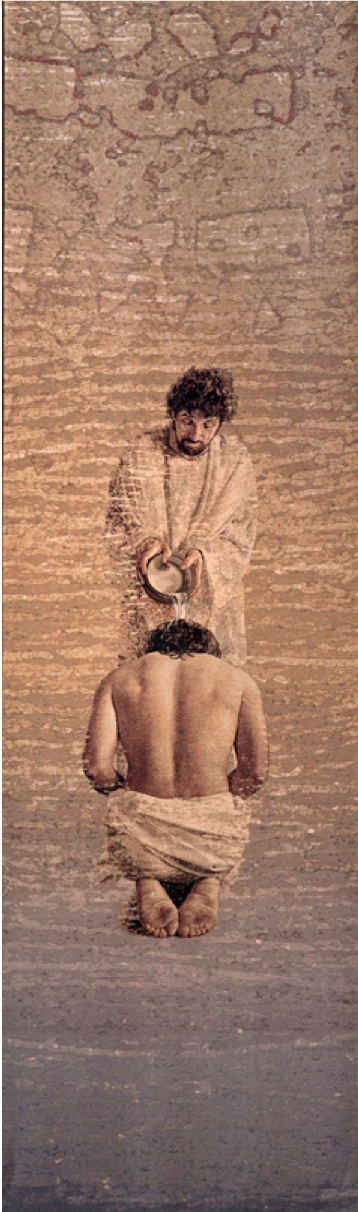

A reflection on Matthew 3:13-17 in observance of The Baptism of Our Lord. Thanks to St. David of Wales for the opportunity to deliver the message yesterday. Jesus was thirty years old when took the plunge. As scripture relates, he sought out his cousin, John, the desert dweller who ate locusts and honey and preached to a good-sized crowd to repent of their sins before he dunked the converts underwater. Matthew’s gospel tells us that John would have prevented Jesus’ baptism, saying, “I need to be baptized by you, and do you come to me?” But that Jesus answered him, “Let it be so now; for it is proper for us in this way to fulfill all righteousness.” It seems an odd statement from Jesus, who doesn’t come across as a man concerned by what is proper. In fact, he’s usually the opposite, setting aside customs and rules that interfere with right relationships. Did propriety really compel Jesus to show up at the river? Or was it something else? There are no Biblical clues. We assume that Jesus already knew his identity as Son of Man, that he was aware he’d been born to a unique destiny, that showing up at the riverbank and submitting to John’s baptism was perhaps a formality, the ceremonial swearing in after God’s election. And soon after his baptism he finds himself on a vision quest in the wilderness battling temptations as he determines how to live out his destiny. But on the day of his baptism Jesus queued up along the riverbank with the other sinners, with nothing in his appearance or reputation signifying to anyone that he was anything other than exactly like them. A person, soon to be wet and repentant, sharing a desire to turn their lives around, or at least to align them more closely with what they perceived in John’s message to be God’s intentions. Whatever private message God had telegraphed to Jesus over the previous thirty years when he sat by firelight sharpening his carpentry tools and contemplating life was confirmed in the light of day along the banks of the Jordan, in front of the crowd, who must have been startled by the resulting thunderclaps, the holy spirit descending as a dove from the clouds, and the booming voice of God announcing his Son’s belovedness. Baptism of water and the Holy Spirit was the first sacrament that Jesus instituted among his followers; the Eucharist was the second. Two thousand years later, public baptism remains the principal Christian rite for those who want to join with Jesus. I assume that most, if not all of us, in this room have been baptized. And most of us have stories about that momentous event the Book of Common Prayer defines as “union with Christ in his death, resurrection, birth into God’s family the Church, forgiveness of sins, and new life in the Holy Spirit” (p. 858). I was twenty-four when I was baptized in 1985, standing in front of a United Methodist congregation of sixty or so people as my pastor dipped his hand into a small bowl of water and touched it to my forehead three times. In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit, he baptized—my bangs. Water never touched my skin. I had thought of baptism as a sin-proof coating like Teflon. Promise to stop doing things my grandmother (the only religious person in my family) would disapprove of, apply water to skin, and after death I wouldn’t burn to a crackly crisp in hell-fire. The words in the United Methodist Hymnal were pretty clear, “Forasmuch as all have sinned and fallen short of the glory of God, our Savior Christ said, ‘Unless one is born of water and the Spirit, one cannot enter the kingdom of heaven.’” It was one thing not to have been baptized when I didn’t believe in God. But, once I was a believer, wasn’t I still in danger of the fiery pit since I hadn’t been adequately spritzed? Sister Ishpriya wrote, “a tiny drop of water can cleanse the whole of my impurity when blessed by your forgiveness. But, O Lord, more than all this, this tiny bit of water passed over my head is the symbol of my birth in You.” A tiny drop of water on my face—Was it too much to ask? “The Baptismal Covenant is God’s word to us, proclaiming our adoption by grace, and our word to God, promising our response of faith and love,” the United Methodist Book of Worship told me. I had done my part with my vows, but I was convinced my pastor had failed in carrying out God’s part and suspected my baptism was a fake, though I’d later learn that Methodists, like Episcopalians, believe that baptism is “permanent and indelible” (Walk in Love p. 25). I smiled when people hugged me after the service, but deep down I worried that I was still flammable. I knew I was God’s, but not because of this ceremony, where there certainly hadn’t been enough water to scrub even a follicle of me clean from sin, but because God had come into my life a few months earlier and arrived while I was in the shower. As I rinsed off the last suds of soap, the water changed. It flowed softer, filling me from inside out with what I can only describe as pure love. This love wasn’t a zingy, romantic pulsing, it was absolute and unconditional, love I’d later feel for my daughters at birth. This love was expansive, excessive, a gift I hadn’t even known I’d asked for. I had no doubt this love came from God, and later, when I came to know the stories, it seemed entirely plausible. If Jesus could turn barrels of water into wine at a wedding reception to please his earthly mother, then his unearthly father could change water to love in my bathroom pipes. When I turned off the faucet and reached for a towel, I felt like a different person, raw and alive, claimed. God loved me and I had to respond. I’d overheard something about leaving everything to follow Jesus. Was I supposed to leave my husband and join a convent, or move to a kibbutz? I decided to attend a peace study at the local United Methodist Church instead. I took a membership class after that appreciated a faith that took into account not simply scripture, but tradition, experience, and reason. I was encouraged to think for myself, something I’d always assumed becoming a Christian would negate. The social principles focused on everything from eradicating poverty and disease, to fair wages and union rights, from racial equality and respect for the environment to opposition to gambling. This care for others was so broad and contrary to the cries I’d heard from Bible thumpers during my college years, and so close to the values I held, that I was prepared to pledge my prayers, presence, gifts and service. The only obstacle to my membership was fact I hadn’t been baptized. It was an easy problem to solve. I didn’t need a class to study biblical accounts and precedents or understand historical or theological reasons for baptism. I only needed a few more questions inserted before my membership vows. My pastor didn’t even tell me specifically how my baptism would be done. If he had, I might have reached up and pushed my bangs to one side. If I’d had access to the Book of Worship then, I would’ve read, United Methodists, like Episcopalians, “may baptize by any of the modes used by Christians. Candidates…have the choice of sprinkling, pouring, or immersion; and pastors and congregations should be prepared to honor requests for baptism in any of these modes.” Knowing that, what mode would I have chosen that might have felt as powerful as my shower experience? By the time my oldest daughter was born in 1988, I’d come to understand that baptism was more about the type of claiming that brought doves to Jesus and unconditional love to my shower––a recognition that we belonged to God—and less about applying two molecules of hydrogen and one of oxygen to human skin as insurance. But I wanted her welcomed into the arms and family of God from the very beginning of her life something so absent in mine, so she was baptized at six months old, though I answered on her before. Like before, I repented of sin and declared Jesus Christ as my Savior. But this time, I pledged to nurture my daughter in Christ’s holy church and was aware of the congregation’s pledge to do the same. The pastor dribbled water on my baby’s mercifully bald head. Jennifer’s scalp wasn’t soaked, but there was no doubt she felt something. Her eyes grew wide. She looked straight at Pastor Lorraine who took Jennifer in her arms, lifted her high overhead and walked down the aisles presenting the newest daughter in Christ. Even now I think sprinkling seems the perfect way to baptize a baby, the water splashing like tears of joy, as we become aware of how precious life is, and how this ritual is not only an offer by flawed human beings to raise a child to know God, but acknowledgment that this young life is as pure and full of possibility and unconditional love as it ever will be. The infant baptism of sprinkling wraps water and spirit and gratitude and enormity into a holy moment filled with unseen and ever present doves and voices. We know the beloved is in our midst, in the form of this tiny person. But sprinkling for me as an adult was a complete bust. I was a Southern California water baby. The first fourteen years of my life if I wasn’t swimming in the community pool, wading and bodysurfing along the shore, or submerged in the bathtub submerged, I was drying off. What type of baptism would feel most like giving up an old life and becoming a new creature? It was more than decade after my baptism that I first saw pouring. Thirty-year-old Shannon, with a purple beach towel wrapped around her neck, received a pitcher of water overhead as she knelt before the altar. The towel took the brunt of the water, but the back of her gauzy dress darkened, and she sat in clammy garments during the remainder of the worship service. I was baptized in November, and even in retrospect, the idea of a quart of water dumped over my head in the midst of a Sunday service on a cold cloudy morning wasn’t appealing. Under the right circumstances, though, pouring does have its appeal. In the Cathedral of our Lady of Angels in Los Angeles, California, “The Baptism of the Lord” is depicted in the center panel of the baptistery tapestries designed and woven by John Nava. This is the image on our bulletin cover today. Against a background of sand that wavers like a mirage, Jesus kneels low, bare backed, head bowed before John. His legs are not immersed in the watery Jordan, but pressed against its gritty bank. John, looking tenderly at his cousin’s submission, pours a bowl of water over Jesus’ head.

The gentle cascade saturates his hair, cools his scalp, refreshes him in the scorching heat. Jesus can feel the small stream of water, each drop sliding over his skin, and in John’s measured pouring he has time to breathe deeply of the significance of this moment. Soon the heavens will open, soon the voice that called us into being will speak to the crowds, and will say of this son, the words we all long to hear, “You are my beloved.” Finally, there is immersion. As much as I’d like to think I’d have chosen immersion, the truth is, even if I’d known it was possible, standing on the banks of the local reservoir while my pastor dunked me into the municipal water supply would’ve been too much spectacle as a fledgling believer. But many years later, I stood with my congregation on a hot Sunday morning as we concluded worship at the edge of a swimming pool to witness ten-year-old Sarah’s baptism. Over their bathing suits, she and our pastor wore white robes that billowed around them as they waded in. Secure in Pastor Margo’s arms, Sara went under, and reemerged soaking, hair plastered to head, watered to the bone. Then, as she climbed out of the pool, water flowing from her robe, we gingerly hugged Sara, trying not to get too wet. “Baptism is both God’s act of grace in the world and the human community’s response to that grace in faith and obedience,” according to the Book of Worship, and Sara’s was close to the way I imagined the experience of those who came to John the Baptist, as they flooded to the Jordan River, eager for sin cleansing and a fresh start. They kicked off their sandals and waded in, gasping a bit when the water slapped against their hips and stomachs. Then they held their breath as John dunked them under. There was the sensation of surrender, closing their eyes, allowing themselves to be submerged, the shock of cool water enveloping them, the smallest sensation of drowning before they surfaced gasping, and stumbled ashore into the arms of family, friends, and even strangers afterward. Before Jesus came on the scene, John warned them that there was more to it, that this was just the beginning. Someone else was coming who was going to baptize with fire. No doubt that branding would sear us into family, scar us for life, leaving marks no one could ignore or forget. Whether the people listened, whether they followed Jesus into the fire or not, there could be no arguing that their baptisms were memorable. In the Methodist tradition, each year on this Sunday when we celebrate the Baptism of the Lord, and each time there is a baptism, we are called to “Remember your Baptism and be thankful.” It wasn’t hard for me to remember mine, but I couldn’t bring myself to be thankful. When I didn’t want to remember my shoddy baptism, I remembered both my daughters’ baptisms, and how meaningful they were to me, though my children have no memory of their baptisms outside photos and stories I’ve given them, and I wonder if I have taken from them the opportunity to remember and be thankful. I’m too new to the Episcopal Church to have experienced many of the traditions that surround this day. But I do know that, as much as we try, we can never do God right. Our sacraments and rituals, the big moments in our lives of faith will always reflect our humanity, our frailties, bad aim, and the things our parents did or didn’t choose for us. My baptism wasn’t the big bang I longed for. But as I look back, I can see the event perfectly illustrated not only my need for God’s grace, but my need to extend grace to my pastor, to the congregation, to God and even to myself. As Gayle Felton writes in This Gift of Water, “Baptism, then, is not so much an event as it is a process…dynamic, not static; a journey, not a destination; a quest, not an acquisition.” Today we come to the water alongside Jesus, who had no need for repentance, but who chose to be baptized, his first step into the river of his destiny. He chose to enter into our human experience entirely, despite his divinity. He became one of us and through his surrender, he was filled with the Holy Spirit, the comforter he would leave with us. With him we step into the river, we submerge under water that envelops us like our first home where we are cradled and blessed before birth, a place we can only occupy momentarily as we hold our breath and float in the weightless present that surrounds us in the expansive love of our Creator, dying to all that would separate us from that love. And when we can bear it no longer, we emerge from the water gasping, blinking, dripping, shivering, filled with the reminder of who we are and whose we are. May, each dip into river, Sound, lake, and stream, may each flume of sea spray, each drop of rain upon our skin, each sprinkling of the shower head and garden hose, each submersion into bath and dishwater, each hand dipped into the baptismal font before worship remind us again and again that we are God’s beloved. And to paraphrase the Book of Common Prayer, may that belovedness raise us to a new life of grace, give us an inquiring and discerning hearts, the courage and will to persevere, and the gift of joy and wonder in all God’s works. Amen. (p. 308)

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

I began blogging about "This or Something Better" in 2011 when my husband and I were discerning what came next in our lives, which turned out to be relocating to Puget Sound from our Native California. My older posts can be found here.

Categories

All

Archives

September 2023

Newsletters |