|

A message for the community of St. David of Wales on Good Friday, April 15, 2022.

I confess that I have never wanted to call this day “good,” that the crucifixion leaves me heartbroken, despite knowing what comes next. I have imagined, time and again, a different story that didn’t require death. Each year as our Holy Week journey takes us closer to the cross, I have hoped against hope that just this once, events would unfold differently, that history would be rewritten, that the powers of church and state would surrender themselves to the radical power of love that Jesus professed and embodied. I have wanted alternative scriptures where, having fully instituted God’s will on earth as in heaven, Jesus retires to Galilee, resumes carpentry, marries, raises a family, and lives to a ripe old age.

0 Comments

A Message on Luke 15: The Parable of the Prodigal Son for the community at St. David of Wales, March 27, 2022

In the New International Version, and many others, this morning’s lesson from Luke is titled “The Story of the Lost Son.” In the Expanded Bible it’s “The Son Who Left Home.” The New Testament for Everyone labels it, “The Parable of the Prodigal: The Father and the Younger Son.” In the Contemporary English Version, the title reads “Two Sons.” And finally, the New Revised Standard Version follows suit with “The Parable of the Prodigal and His Brother.” No matter how we refer to it, this longest of Jesus’ parables which appears only in Luke’s gospel, has resonated deeply over the centuries, perhaps more than any other story Jesus told. And it still speaks to us in circles far beyond the church. Even as a secular child, I’d heard of the prodigal son—and even without knowing that the word prodigal (it’s something like recklessly wasteful), I knew the son was up to no good. A Message delivered to St. David of Wales Episcopal Church on Luke 6:17-26

Luke’s gospel leaves no doubt that Jesus has come to turn the powers of the world upside down. When our readings for this liturgical year turned to Luke’s gospel in Advent, we heard the promises of God’s plan through the song of Mary. Upon learning that she would give birth to the Messiah, Mary—an unwed teen in occupied territory—proclaimed that she had found favor with God, that God had lifted up the humble, and fed the hungry, while casting down the powerful and sending the rich away hungry. A few weeks ago, when we read of Jesus beginning his public ministry, we found him in his hometown synagogue reading from the scroll of Isaiah and proclaiming that he was the one sent to free the oppressed. And in this morning’s gospel lesson, Jesus offers blessings to “comfort the afflicted” and woes “to afflict the comfortable” as the saying goes. A reflection on Luke 21:25-36 for the community of St. David of Wales Episcopal Church, Shelton, WA. First Sunday of Advent, November 28, 2021.

Everybody is ready for Christmas. The Thanksgiving leftovers that crowd our refrigerators are almost all gone. Radio stations are playing Christmas songs 24 hours a day. Stores have been stocked with holiday décor and gifts since Halloween. Black Friday sales flooded our email inboxes this weekend. Neighbors are stringing up lights and inflating super-sized Santas. Everybody is ready to celebrate, except us. We who worship Christ and follow the church calendar have flipped the page to the first day of a new year that begins not with decorations, celebratory champagne, and countdowns, but with weeks of waiting. And what a strange sort of waiting it is. We wait for what was promised and what has already occurred. We wait for a sign that God is with us. We wait for God to break into human history with the birth of Jesus. And we wait for what was promised but has yet to be fulfilled. We wait for the final redemption of humanity and all of creation. We wait for peace and justice to prevail throughout the earth. We wait for the Son of Man to come again in power and glory. A reflection on Mark 10:46-52 for the community of St. David of Wales, Shelton, WA, October 23, 2021.

In this morning’s Gospel passage, Jesus is in Jericho with his disciples surrounded by scores of people. Everywhere he goes, Jesus has been attracting attention with his healing and teaching, and now it’s a parade-like atmosphere, with Jesus as the featured attraction as he and his followers, and many of the faithful leave the city to make their way to Jerusalem to observe the Passover. Jesus will leave this city never to return. He will enter Jerusalem and the sweep of events in the coming days will lead the throngs from celebrating his power and popularity to witnessing his execution. Bartimaeus, a blind beggar, appears in the commotion. The fact that he is named, unlike so many whom Jesus has healed, is significant. Bartimaeus, or his father Timaeus, may have been well known in the community before the encounter, or Bartimaeus may have been recognized later as part of the new church formed after Jesus’ death. And the story of Blind Bartimaeus is familiar to many of us, one enacted gleefully by blindfolded Sunday school students, who leap and stumble, hands extended, crashing into their friends as they grope toward Jesus. A Reflection on Mark 6:14-29 for the community at St. David of Wales Episcopal Church. July 11, 2021.

What a celebration the season of Pentecost has been for our church community with the return of in-person worship. Even masked and humming our hymns, I know we’re all grateful to see more than a handful of humans after so many months of YouTube church. After the service last Sunday, I had the blessing of a long conversation in the parking lot with a member who spoke of the assurance that God had given her in the midst of difficult circumstances, and of God’s faithfulness in the work of grief and healing. I drove away dripping with gratitude for the ability of worship to bring us close to one another, thankful for the way gathering together on Sunday mornings provides opportunities to share with each other the stories of how we live out our faith day-to-day. In this Pentecost season of coming together, we’ve been traveling with Jesus and the disciples as they’ve too have come together, immersed in the growth of Jesus’ ministry, witnessing the crowds gathering to listen and learn, hungry for the hope and healing Jesus offers. We’ve seen religious leaders question and challenge Jesus, and the assurance with which he responds, reminding them of who we ultimately answer to. As people are converted, the countryside is abuzz. Last Sunday, we read of the disciples being sent out on their own filled with the power Jesus bestows, and we’re eagerly anticipating their return, waiting to hear about their adventures. But today, Mark interrupts his regularly scheduled message of empowerment with a horror story. When I told my prayer partner that I was going to be preaching about the beheading of John the Baptist, she immediately mentioned King Henry the VIII. At first reading, it does seem like today’s gospel passage is a script for a mini-series, a look back at political figures, like Herod, who are little more than footnotes in our history, rulers whose power and influence were fleeting. After all, it is in Jesus’ name we gather, not the in name of Herod or Caesar or Henry or any other ruler. At first glance, we can read this passage and breathe a sigh of relief, thankful that people are no longer so barbaric. Yet even a cursory glance at current day headlines leaves no doubt that not much has changed since Jesus’ time. But when I think about silencing critics, we do that all the time on social media, unfriending people left and right. And the rich and powerful elite everywhere still cling desperately to power by silencing those who speak the truth through arrest, execution, assassination, court decisions, legislation, and terror. It can be comforting to think that we’re not like Herod, after all, not one of us will ever be governing a territory or divorcing our wives to marry our brother’s wife for political gain. We aren’t going to jail a prophet whose views we otherwise find intriguing because he speaks out against the inappropriateness of our marriage. We aren’t going to be throwing an extravagant birthday party where we bribe our daughter to dance in front of an audience of inebriated men by promising her anything she wants. And we certainly aren’t going to behead the jailed prophet because we’re more concerned about not seeming weak or wishy-washy in front of our guests, than we are about the prophet’s life. We can think that we’d never be as manipulative as Herodias plotting to kill our harshest critic, or as easily manipulated as their daughter asking for something as horrifying as murder and the parading of a man’s severed head at a party. Out in the world running errands, or at home with my husband and cats, it’s easy enough to think that I'm a good person. After all, I’m never intentionally evil like the villains I see in TV shows. But when I look honestly at my own life, I can find plenty of instances over the years where I have behaved like Herod, Herodias, and the daughter, albeit on a much smaller scale. I’ve been told how my behavior has hurt others but have refused to take responsibility for my actions or change my ways out of fear and a desire to protect my self-image. I’ve manipulated others to get what I want, trying to control people’s actions, believing they had to change their behavior in situations that were uncomfortable for me, rather than changing my behavior or learning to respond to circumstances differently. I have wanted to hold onto the power and prestige I’ve had in certain roles that I was given by virtue of title, rather than by having earned genuine respect. I’ve made decisions that have gone against my own conscience in a desire to protect the status quo and preserve the semblance of peace in my life when change was needed. You can probably find some parallels in your own lives as well. For better or worse, none of us can escape acting like humans. But how do we move forward once we realize we’ve caused harm? Jesus said that “those who want to save their life will lose it, and those who lose their life for my sake, and for the sake of the gospel, will save it.” When the news of Jesus’ ministry reached Herod, Herod thought that John had been raised from the dead. Imagine for a moment what might have happened if Herod had then tried to atone for John’s death. What if Herod had gone to Jesus and talked with him? He might have become one of Jesus’ disciples. Instead, he became part of yet another execution and silencing of God. In its own way, this passage asks us to examine the worst in human behavior so that we might reorder our lives. It challenges us to give up our desire for power and control, to name the brokenness and injustice in our governments, to admit the shortcomings of our social structures that leave many in aching need, to recognize the ineffectiveness of our ego-driven efforts, and to acknowledge the pain we cause one another simply by thinking of our own welfare before we consider the welfare of others and the welfare of the earth itself. Confession, even when it’s silent, can be uncomfortable, and it’s something we rarely do outside religious circles. Even inside religious circles, confession is something that is skipped very often in my former denomination and in many others. Thankfully, we in the Episcopal church follow a worship liturgy that is relatively unchanging. Every week, whether we gather in person or virtually, we are called to repentance, we are called to turn away from the world, and to turn toward God as we stand before one another and confess our sin, both societal and personal. We bring into the light those thoughts and actions done, and those left undone. We offer those thoughts and actions of which we are aware, and those known only to God. We lay bare our need for forgiveness, and we open ourselves to Christ’s healing power and the transformation it brings. In short, we endeavor to lose our lives for the sake of the gospel in order to save them. Two thousand years after Jesus and his followers spread the good news throughout Galilee, we are still too much like Herod, yet we know he appears in the gospel as a cautionary tale, as a stark reminder of what happens when we invest all our hope in human power and authority. Two thousand years later, the reign of God has not yet come to fruition, but it is the home and hope our hearts long for. We are still listening to Jesus’ words, still being shaped by the stories he told, still remembering the lives he changed, then and now. We are still following, still stumbling, still getting up and starting over, still on the path toward the abundant life God offers to the entire human family. What an incredible gift this journey is. And what a blessing to be part of this faith community, to walk this road together, to make our way closer to Christ together. The wildest thing happened a week ago. I was making dinner in the kitchen, talking to my husband who was standing at the counter when we heard a tremendous amount of avian racket outside. Kevin looked out the living room window and saw a bald eagle take down a great blue heron mid-flight and land in the water. I ran out of the kitchen and we both watched through the windows as the eagle swam, using its wings to “freestyle” struggling to stay above water while it dragged the heron along underwater in its talons toward our beach. My camera was upstairs, and once the eagle made it to shore, I ran to get it. I opened the bathroom window, popped out the screen and snapped a few hundred photos (sports mode) from there of the eagle eating its prey on the oyster bed just at the edge of our beach. I usually take wildlife photos through my windows since opening doors and windows almost always causes them to scatter, but I didn’t want glass in the way of this rare sight. Great blue herons eat a fair number of critters eagles eat, and eagles usually only go for nestlings, though a local resident noted he’s been watching one pair of eagles hunt herons for the past few years, and they’re now teaching their juveniles to do so as well. The eagle looked in my direction, but it stayed put, not wanting to leave its kill. Watching it stand atop the heron, and tear into it, spitting out feathers was like watching a nature documentary that spares nothing. When the eagle moved off as its mate approached, the heron sat up, and it was then that I realized the poor bird was alive while being consumed. Kevin, who was still in the living room watching, had to step away at this. But I kept on snapping, looking through my camera, thankful it served as a filter that gave me some distance as I became a documentarian of this disturbing yet fascinating moment in the circle of life. I usually photograph sunsets, mountains, rainbows, gorgeous watery reflections, and wildlife in attractive poses because I live in a place abundant with natural beauty. But there is another side to life in paradise that involves violence. Violence necessary for survival which I as a human carnivore can blithely ignore since others kill and butcher meat for me. My only struggle is in following recipes. I'm humbled and fortunate to have witnessed the food chain in action without even seeking it out.

A message given on the seventh Sunday of Easter, May 16, 2021, for St. David of Wales Episcopal Church, Shelton WA. Gospel: John 17:6-19. Today’s gospel reading takes place on Jesus’ last night with his disciples. After washing their feet, he has spoken to them about what is to come, for him, and for them, and we have heard some of these words in recent Sundays in Jesus’ metaphor of the true vine and branches and his commandment to love one another as he has loved them. In John’s gospel, 7 chapters are devoted to Jesus with his disciples in the Upper Room. Knowing that his time with them is swiftly drawing to a close, Jesus has done everything he can to prepare his disciples to live without him. And after he has said and done all that, he turns to the one who sent him and prays for his dearest friends, those he has travelled with, those who have borne witness to his ministry, those who will somehow carry on his name, those who have become his family. This prayer is different from the prayer he gave his disciples when they asked them how to pray. This prayer is less linear. It moves back and forth over the same themes, like a poem or tapestry, with words or stitches repeated with subtle changes that add texture and nuance to the meaning. Let’s listen to some of these themes. Jesus utters words of giving and receiving: you gave them to me everything you have given me the words that you gave to me I have given to them on behalf of those whom you gave me I have given them your word, they have received them Jesus speaks of being sent: they have believed that you sent me I am coming to you now I am coming to you As you have sent me into the world, so I have sent them into the world He speaks of being glorified, and sanctified: and I have been glorified in them Sanctify them in the truth for their sakes I sanctify myself, so that they also may be sanctified in truth He speaks of protection: protect them in your name I protected them in your name I guarded them protect them from the evil one And of the world: I am not asking on behalf of the world now I am no longer in the world, but they are in the world, I speak these things in the world the world has hated them because they do not belong to the world, just as I do not belong to the world I am not asking you to take them out of the world As you have sent me into the world, so I have sent them into the world. And He speaks of belonging: They were yours that they may be one, as we are one All mine are yours, and yours are mine Jesus’ prayer comes after his last supper with his friends, after he has said much to them, and before they leave the house for the garden where he’ll be arrested. Here, he turns his heart and mind inward to pray. Our reading drops into the prayer after the 5th verse, and the prayer continues through verse 25. The verse that follows our reading, the 20th, offers important context for us. Jesus continues with these words: “I ask not only on behalf of these, but also on behalf of those who will believe in me through their word, 21 that they may all be one.” Jesus prays for those beyond the circle gathered around him. He prays for those who will believe in him through his disciples’ word. That is every single person who has come to believe in Christ after his death. That’s two thousand years and millions of people. That is you and me. Jesus prays for us. Jesus asks all these things on our behalf. He wants protection and unity for all people. He wants us to receive and give God’s gifts and to spread God’s truth into the world. This is not a small private prayer; this is an expansive all-encompassing prayer. Even with the threat of death looming, Jesus doesn’t allow fear or anxiety to turn his focus inward, as it would for many of us. He focus on caring for those he loves. His words and actions model for us how to stay present and grounded in the reality of God when the powers of the world have an agenda that seeks to squelch and silence God’s truth. Jesus models for us how to stay present to and aware of those who look to us, even while we struggle with our own pain, fear, and doubt. He models for us how to do what is in our power, and how to turn to God in trust for so much of life that is beyond our control. He shows us how to love well and how to say goodbye in a way that honors life even in the midst of grief. His prayer reminds us that though we do not belong to the world we are in the world—For better or worse. “For God so loved the world, that he gave his only Son, so that everyone who believes in him may not perish but may have eternal life,” John tells us in 3:16. God loves this planet and all of creation. The mountains, valleys, seas, and deserts, and creatures that inhabit these places. And God sent Jesus, who in turn sent his disciples, who in turn sent us, into this beautiful and broken world. A world corrupted by human sin and greed, by ignorance and apathy. A world that yearns for peace and groans for justice. A world that sustains all life, that still shimmers with kindness and love. To be alive is to be fully immersed in this world. Breathing its air, eating its food, creating new life, transforming the resources offered up by the good earth, exchanging goods and services, developing cultures and societies, and endeavoring to live peacefully with our neighbors. There is no denying our physicality and the suffering and death that are an inevitable part of the human experience. And yet, our true identities are not based on worldly measures: social security numbers, credit scores, property deeds, or retirement benefits. Our true identities aren’t tied to diseases or diagnoses. Our true worth is not measured in W-2s, job titles, degrees awarded, trophies on shelves, plaques on our walls, the number of children or grandchildren we have, mountains climbed, illnesses survived, church committees chaired, or pious acts performed. Our identities and our worth are determined by only this: The fact that we belong to God. The fact that we belong to Jesus. And in those facts, the undeniable reality that we belong to each other. “You belong to God. You are beloved. You matter.” These are the words we are called to speak in this world. These are the words of hope and comfort we can offer to those we befriend easily, and those we find difficult, those riddled with hopelessness and despair, those who are “failing” by the standards of the world, those forlorn and forgotten, those caught in the grip of systemic poverty and injustice, those crippled by racism, sexism, and the many -isms that constrain our spirits, those who seem to “have it all” in celebrity or success, yet feel nothing but hollow. Jesus’ prayer sends those he prays for straight into the world where we can give each other his truth. And that’s not easy for those of us who doubt our own voices, or fear conflict, or are introverts. And it’s not easy for any of us who’ve been sequestered in this COVID year and don’t feel comfortable having these conversations electronically. May we receive the gift of this prayer and may it empower us. As we embrace the gift of this prayer, may we carry Jesus’ wish for our protection and assurance of our belonging close to our hearts. And wherever we are sent, let us send these words, too so that all might receive their reassurance and promise. When the needs and demands of living in this world threaten to overwhelm us, we need only to remember that God is the foundation of the world and the very center of our being. Our true home as we live in this world but are not fully of it. In his prayer Jesus say to the holy one who sent him, “now I am coming to you, and I speak these things in the world so that they [meaning his followers, meaning us] may have my joy made complete in themselves.” May our joy truly be complete in Christ’s indwelling presence. A meditation for the community of St. David of Wales Episcopal Church in Shelton, WA. Given on Palm - Passion Sunday, March 28, 2021.

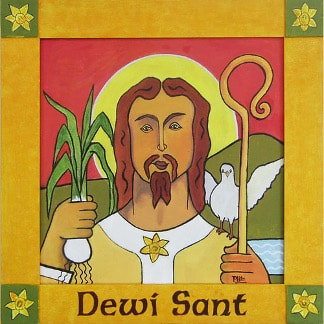

Our observance of Palm Sunday begins with so much hope. Jesus rides into Jerusalem on the back of an unbroken colt. An action he has deliberately chosen. An action reserved for rulers. Crowds cheer him on throwing their coats into the road and waving branches before his path. They shout Hosannas and bless the one who has come to set them free from Roman oppression. And yet this Sunday always moves us to the cross. Jesus arrested, tortured, murdered. It’s a hard place to be. Last Sunday Father Duane said in his sermon that as Jesus set his focus on Jerusalem, his goal was death. I’d never heard it said in those exact words, and it was such a startling statement that I wanted to protest. Surely, I thought, Jesus’s goal was something else. He was going to Jerusalem to spread the Good News like he had around the countryside. He was going to preach, and teach, and heal, and gather up followers. Right? Wrong. Jesus was going to the seat of religious power to speak truth to that power. And he knew the confrontation would lead to his death. He had told his disciples as much. And they didn’t want to believe it; they didn’t know how to believe it. And I am exactly like the disciples. Every year as we enter Holy Week, I wish for a different outcome, as if the Gospels have morphed into a “choose your own adventure” book, and I can write a different ending, an ending where the religious leaders have their eyes opened to the ways they’ve corrupted God’s word. An ending where they invite Jesus to lead them in a complete overhaul of the church, and give up their power for the good of others. An ending where God’s kingdom comes, where God’s will is done on earth right then. An ending where Jesus not only gets to live, but gets to live happily ever after. My ending is a fantasy born of love, and naivete, and self-protection. Love, because it’s been my practice as we move through Holy Week to identify with Jesus and his suffering. And out of love, I want to spare him from this violent death and emotional pain. Naivete, because I have not wanted to believe that those in power would go to such extremes when threatened. I wanted to think that their response was an aberration. And self-protection, because if I could somehow erase the crucifixion, if I could somehow make it unnecessary, then I could feel safe. I wouldn’t have to confront my own discomfort at the injustices in the world, I wouldn’t have to face my complicity in systems that oppress others, and I could ignore my failure to be like Jesus, my unwillingness to sacrifice my life for God. Unless we’re brand new to the faith, we come to the edge of Holy Week with the experience of having cycled through this liturgical season before. We come with expectations about how we will carry the weight of this week along with living in a world that largely carries on without marking its significance. We hold the tension of Jesus journeying toward death, while we live with the gift of the Resurrection. And we approach this week with rituals, both personal and communal for observing the critical events in our religious heritage. Lat year we observed Holy Week in lockdown. This year we approach at what I pray is the beginning of the end of the pandemic, as more and more of us are vaccinated against COVID-19, as the counties in our state move into Phase 3 of reopening. And as our vestry plans and prepares for St. David’s to safely reopen for in person worship. We have spent more than a year in the wilderness, isolated from one another, all the small things we once did without thinking, like sitting in crowds and hugging, have become magnified. We have lived through a year that has also magnified our brokenness and shone a spotlight on our sinful human nature. And without our ability to gather safely, these events have left many of us feeling powerless. COVID-19 has killed 2.77 million people worldwide, claiming over half a million in the U.S. Systemic racism and the murder of Black Americans as a law enforcement response has been exposed in ways that we with white privilege can no longer ignore. Hate crimes against Asian Americans and mass shootings have filled our newsfeeds in recent weeks. Christian Nationalism has hijacked everything Jesus stood for. And those at the highest levels of power in our government, responded to election results with denial, invented claims of voter fraud, and insurrection. When those tactics failed, they began a campaign of voter suppression legislation in states across the country. In Georgia, it is now a crime to offer water to voters waiting in line. More than ever before I see how much the injustice in our time and place looks like the injustice in Jesus’s time and place. As much as I’ve wanted to believe in progress, I find the present mirroring the past. And for me, that means confronting the reality that we are still in desperate need of Jesus’s sacrifice. It means coming to terms with the fact, that like the disciples, I do not know how to accompany Jesus all the way to the cross or to stay with him until his death. Like the disciples, I do not know what to do when everything looks like it’s going to hell and I can’t stop it. In our natural fight, flight, or freeze response, both the disciples and I opt for flight and freeze. Like the disciples, I don’t know what to say, so I keep quiet when I ought to speak up. Like the disciples, I’m not brave enough to risk the consequences of speaking truth to power, so I run for safety. And like the disciples, I abandon Jesus in his final hours when bearing witness to his pain feels just too difficult. To accept the inevitability of Jesus’s sacrifice means also to accept the inevitability of the disciples’ failure. And to accept the inevitability of the disciples’ failure, means to accept the inevitability of my own failure. And that is so difficult. I want so very much not to fail. I want so very much to love God with all my heart, soul, and mind. I want to emulate Jesus. Except when I don’t. Except when I’m too frightened, too tired, too lazy, too distracted, too upset, too confused. Too… In short, I always fall short. And I always will. Thankfully, the crucifixion is not the end of the story. And in many ways, it’s just the beginning of the disciples’ story. But I don’t want to jump too far ahead. I want to carry my palm branch along with my own weakness. I want to honor this king riding into Jerusalem on a borrowed colt, this one who gave up power in order to empower others, who sacrificed his rights rather than insist upon them, who challenged us to find comfort and safety by letting go of our striving. I want to hold that image of Jesus buoyed by the triumphant crowd before we all failed him. Despite the coming fiasco, despite our well-intentioned betrayal, despite everything that will happen next, I know in that moment, looking at Jesus, we will see in his eyes the hint of forgiveness and the shimmer of God’s eternal promise. Image by Poppy Thorpe at Pixabay. A meditation on Mark 8:31-38, and a celebration of St. David's Day, for the community of St. David of Wales Episcopal Church in Shelton, February 28, 2021. I find it so fitting that on this Sunday—my first after officially becoming Episcopalian—we’re celebrating the feast day of Saint David of Wales after whom this church is named. Honoring the saints is definitely an Episcopalian and Catholic tradition; something that is new to me and isn’t practiced in Protestant denominations—including the United Methodist where I participated for 35 years. I first worshipped here at Saint David’s on the morning of Pentecost in 2018. Before I came, I perused the church website and read the entry about Saint David, learning a little about his history. After worshipping here that first time, I Googled Saint David of Wales himself, and read that in addition to being the patron saint of Wales, he’s the patron saint of poets and vegetarians. I’m a poet and my youngest daughter is a lifelong vegetarian, so I thought with those connections to the Saint, I was ready to make my spiritual home here. And while congregational life isn’t organized around poetry and vegetarian fare, you welcomed my gifts of poetry in our worship services and bulletins; and I’ve tasted plenty of delicious vegetarian offerings at coffee hour. Saint David, who lived in sixth century, was known for his austerity. He founded several monasteries where the monks ate no meat, ploughed the fields by hand without the help of animals, and drank only water—no beer brewing like the happy monks in Bavaria. And David is usually pictured with a leek, since legend has it that he ordered his soldiers to wear a leek on their helmets in a battle against pagan Saxon invaders. The most famous miracle associated with St David took place when he was preaching to a large crowd. When people at the fringes complained that they could not hear him, the ground on which he stood rose up to form a hill. And then a white dove settled on his shoulder. There’s something about this miracle that delights me. There’s no spontaneous bleeding, visions, or delirium, that many “flashier” saints suffered. This miracle is physical and earthbound—a small earthquake rumbling and shaking the crowd as the ground around David rises up into a hill. And it such a considerate miracle in an era before the advent of microphones and sound systems. After the ground is rearranged, a dove alights on David’s shoulder, reminding the crowds of the dove that descended at Jesus’s baptism. The dove signifies God’s presence with David as God’s word flows through him, and reaches all those who want to hear. We don’t know what David said, or how his words, once his listeners could hear them, impacted or changed their lives, but we can picture the scene, just as we can picture the Biblical scenes with Jesus speaking to crowds of thousands. The eighth chapter of Mark’s Gospel begins with Jesus feeding 4,000 with a handful of loaves and fishes astonishing his disciples. The power in this act, coming on the heels of Jesus healing all the afflicted he encounters, has Peter boldly declaring that Jesus is the Messiah in the verses just before today’s reading. And in today’s reading, Jesus tells his closest followers the fate that lies before him for the first time. Suffering and death and rising after three days. No one understands what that rising is going to mean, but everyone understands what suffering and death mean. And it can’t be so. Peter is the one to say “No!” but I’m sure he’s speaking for all the disciples. They have been drawn to Jesus who is filled with life, and light, and wisdom, and power. They have been mentored and empowered by Jesus, and sent out to spread the Good News of God’s kingdom that they’ve heard him speak about. They’ve healed people in his name. They don’t just admire and respect Jesus. They’ve left behind their old lives, their jobs and families, and have ordered their very existence around him. They have become community lead by this man they have come to love deeply. We can imagine the words in Peter’s rebuke to Jesus: “No, don’t say that!” he blurts out. “That can’t happen. There has to be another way. A way to keep you safe. A way to keep doing God’s work with you here with us. Maybe if we lay low for a little while. Go back to fishing until the Pharisees calm down. Or maybe we find a blacksmith, forge some swords, build a small army, and attack those who would attack you.” Peter so often gets a bad rap for his impulsiveness, his failure to look ahead and see the big picture, his wild swings from proclamation to denial, but the way I see it, Peter is just like us. Sometimes we get it and see God at work in the world. Sometimes we can open ourselves to the unfamiliar and frightening as we step out with hope and faith to do what seems impossible; sometimes we’re stuck because we can’t move beyond our own needs, wants, and fears. Sometimes we act thoughtlessly with hostility, destroying what threatens us, and causing unnecessary harm in the name of self-protection. Some people say that the disciples were disappointed because they wanted a warrior messiah who would win with violence. But I see in Peter’s rebuke the same reaction we have when we learn that someone we love is suffering and might perhaps die. We learn of a cancer diagnosis or an assault. Our first thought is “No!” Maybe we scream it; maybe we weep it. We think about fighting back, and cast about for ways to stop the pain for those we love. We’ll move to another city that has the best of what our loved one needs, or where they’ll have a clean slate to start over. We’ll quit our jobs; we’ll radically change diets and habits. We’ll make bargains as we pray. We’ll do anything to change the outcome. Because we love and because it is easier to bear our own suffering than to bear the suffering of someone we love. “Get behind me, Satan,” Jesus says. Not because Peter is wicked or evil, but because Peter’s words tempt Jesus. Peter argues with Jesus presenting alternatives to suffering where Jesus might still usher in the kingdom of God. Peter tempts Jesus the same way Satan tempted Jesus in the wilderness, with scenarios that are strongly appealing. True temptation isn’t just turning down a second slice of cake and reaching for a celery stick, or saying no to something you don’t really want; it’s wrestling with something you want desperately, something you can imagine happening. It’s confronting core aspects of our identities, and having to live with the consequences of our actions whether we stay true to our deepest-god-infused-selves, or whether we succumb to temptation out of fear, guilt, self-doubt, or even love. I hear Jesus’s “Get behind me, Satan,” not only as a rebuke to Peter, but as a rebuke I ought to say to myself on Jesus’s behalf whenever I let fear tempt me into staying small and keeping quiet, flying under the radar so I don’t make waves or upset others who won’t agree with me; or whenever I’m tempted to speak and act with hatred and disgust and the desire for those I disagree with to suffer because those I love are suffering as a result of their actions. All the temptations that come to me obscure God’s truth and desires for me. Jesus tells Peter he is setting is mind on human things, not divine things, and then calls to the larger crowd that gathers round, and gives them and us some hard teachings. Jesus says that to live fully we must give up our insistence on being right. We must set aside our desires to live according to our own plans, and let the Spirit lead us. He tells us that social status and the accumulation of things will never satisfy our souls. He warns us that living only for ourselves brings death. And he says that living for the good of others is the only path that brings abundant life. He tells us to embrace our own suffering, rather than running from or trying to numb the pain that is part of being human and alive. I don’t know about you, but I need this reminder over and over again. Take up my cross. Lose my own life. Set my ego aside. I need Jesus’s words to counteract the words of the culture, the words of advertisers, the words of social media, the words of politicians, the words of celebrities, the words of family, friends, and even myself when I’m tempted by promises of ease and prosperity, and social status; when I’m tempted by fear—fear of the other, fear of failure, fear of the unknown, fear of being alone… The disciples needed to hear Jesus’s words, too, even if their first reaction was “No!” The crowds around Jesus needed those words to learn how to order their lives, because they too, would not always have Jesus with them. The crowds around Saint David needed to hear Jesus’ words six hundred years later. Words that led to life when the hill rose up from the ground so all could hear. The crowds don’t always have to be large. As Jesus said, “Whenever two or three are gathered in my name…” I wanted to become part of the Episcopal Church and this community of Saint David’s, because I need to gather in Jesus’s name and hear his words in the context of a community that inspires and empowers me to live out my faith, a place where I am surrounded by other ordinary yet extra-ordinary people who seek to be faithful to Jesus’s words and God’s call on their lives in ways large and small. Legend has it that Saint David’s last words to his followers came from a sermon he gave on the previous Sunday: “Be joyful, keep the faith, and do the little things that you have heard and seen me do.” Ah, we need the Saint’s words alongside those of Jesus: Take up your cross and be joyful. Lose your life for the sake of the gospel and keep the faith. Deny yourself and do the little things for the sake of others. Amen. I was received into the Episcopal church with two others shown here with the Right Rev. Greg Rickel, Bishop of the Diocese of Olympia,& St. David of Wales' rector Rev. Duane Fister.

|

I began blogging about "This or Something Better" in 2011 when my husband and I were discerning what came next in our lives, which turned out to be relocating to Puget Sound from our Native California. My older posts can be found here.

Categories

All

Archives

September 2023

Newsletters |

||||||