|

A meditation on the gospel passage Mark 1: 14-20, for the community of St. David of Wales Episcopal Church, Shelton WA. January 24, 2021, the third Sunday of the Epiphany.

When I was about twelve and staying at my dad’s house for a week, I came down with the flu, and had nothing to do but lay in bed all day and read while he and my stepmom were at work. So I reached for the Readers’ Digest Condensed version of Tom Sawyer on the shelf in the guest room. I read every word in that edition, but I never read an unabridged version, and have no idea if I missed anything important to the story. For me, the Gospel of Mark is a little like that book on my dad’s shelf. When compared to the other gospels, Mark reads like a Readers’ Digest Condensed yet Urgent version. A “just the facts ma’am” account where the details of what happens are spare, and whatever occurs always happens immediately. As someone who wasn’t raised in a church, my first exposure to Bible stories came, when, as a new Christian and churchgoer, I began teaching Sunday school to first and second graders, relying on Cokesbury curriculum provided by the United Methodist church. I don’t remember now in which gospel I first encountered the story of these four fishermen being called to follow Jesus, but I do know that I, along with my little class, cut out construction paper fish with paper punched holes at the mouth, tossed them onto a butcher paper river on the floor and began to fish with poles consisting of pencils, string, and paper clip hooks. We were all surprised by Jesus, the bold stranger wandering by who called out for us to drop everything and follow him and start fishing for people. Startled though we were, we dropped our poles in the river, and marched out the classroom door following the student selected to play Jesus, who led us down the hall and toward the playground. And I will confess that in the almost 35 years since then, encountering the call story of those first disciples in all four gospels, I don’t remember comparing or compiling the stories into a larger narrative, or putting them on a timeline — though it’s entirely possible I did that in a year-long adult Disciple Bible Study class when my children were young, and their needs and lives were the focus of my life and learning. For me the Bible was full of impossible things that had happened: Moses being found in a basket in the river, Mary becoming pregnant with Jesus sans the usual method, Jesus rising from the dead and later appearing to his friends before he beamed up to heaven. Dropping everything to follow Jesus the second you’d met him seemed no less miraculous. Even in my own life, God had done what seemed impossible, pouring love over me one morning in my mid-twenties while I showered. God’s appearance had seemed sudden and out of the blue, as did my attendance at church the next Sunday, the first time I’d ever set foot in a church since childhood when I occasionally tagged along with friends or grandparents. But God didn’t really appear to me out of the blue. I’d been aware of the hole in my life even before my parents split up when I was nine; and I’d been trying to fill that void with friends, studies, sports, and later activism, work, and boys. In the months before my shower conversion, I’d begun to listen, rather than scoff and dismiss, when those I admired mentioned God, Jesus, and faith. And I’d even done a little reading, not the Bible, but some evangelistic pamphlets that came my way. All this to say, that when God showed up in my shower, I was ready to receive and respond. Maybe God had come by before and called and I’d been too busy with school or work or preoccupied with surviving yet another parental divorce to notice. Maybe those Sundays when I’d felt like an interloper at church, God had managed to leave behind tiny snippets of God’s word that lingered beneath my memories of feeling alone and outcast. I don’t know. But what I do know now, is that when Jesus shows up on the shores of Lake Galilee in today’s gospel reading and calls to Andrew and Simon, he is not a stranger appearing out of thin air making an outrageous request without context. Jesus knows Andrew and Simon. In fact, they have already been following him. In the first chapter of John’s gospel, we learn that Andrew was a disciple of John the Baptist’s, and when John announces that Jesus is the “Lamb of God” [John 1:36], Andrew goes to find his brother Simon, and says to him, “We have found the Messiah” [John 1:42]. At some point before John is arrested, Andrew and Simon return home and go back to work fishing. Perhaps they told Jesus they had to leave, or perhaps he told them go home to get things in order and said he’d come for them when the time was right. They’re still followers of Jesus, but they’re also attending to their livelihoods. As for James and John, they’re fishing with their father, Zebedee, alongside, or at least nearby, Andrew and Simon. Some scholars speculate that James and John were business partners with Zebedee and his sons, who also are successful enough to have hired workers on their boats. It’s entirely possible that they also were already acquainted with Jesus, and perhaps already following him. Other historians guess, based on the brief mentions in the gospels of women who are following and supporting Jesus’ ministry, that James and John were Jesus’s cousins; that their mother and Jesus’s mother Mary were sisters, and that they were well known to one another. Today’s scripture opens with Jesus beginning his public ministry, “After John was arrested, Jesus came to Galilee, proclaiming the good news of God, and saying, ‘The time is fulfilled, and the kingdom of God has come near; repent, and believe in the good news.’” It takes time, traveling through the region on foot, stopping every day to talk with people about change. The task at hand feels urgent, and it’s not something Jesus can do alone, so when he reaches the sea, he asks his fishermen friends to leave their jobs and follow him. He asks them to fish for people. To tell those they meet about God’s heart for the poor, about God’s desire for justice, about a God whose claim on your life is unlike an Emperor’s, it inspires but never demands allegiance. I don’t know about you, but knowing that there are relationships in place at the time of Jesus’s call to the fishermen offers me a sense of relief. The idea of leaving behind your entire life to say yes to the beckoning of a total stranger with a superhuman charismatic forcefield seems to be either an impossible to live up to act of faith and courage, or an absurdly foolhardy and dangerous endeavor. I couldn’t do it. I wouldn’t do it. But the idea of leaving your job, or of leaving your business in capable hands to commit your life to the cause of reconciliation and justice and the ushering forth of God’s kingdom on earth, a cause you’ve been thinking about, and dreaming about, in the company of a person who teaches, motivates, and inspires you to think and dream, that’s another matter. That’s an action I want to emulate. Dramatic. Emphatic. Urgent. Mark’s account of Jesus calling the first disciples is filled with these elements. Mark has an audience, and a purpose, and knows that time is of the essence. And yet, from our place more than two thousand years after these events, we need more than the origin stories of our faith — the gospel accounts of how Jesus’ ministry began and how it ended just three years later. We need more than the Acts of the Apostles and the letters sent to the earliest Christian communities as they formed and ministered and struggled. We need more than the stories of the saints and martyrs of yore. We need the ongoing stories of how we, as ordinary everyday people answer God’s call over sixty, or seventy, eighty, or ninety years. We need stories of how to repent from the values of culture and society that discount human dignity, how to repent from the worship of the church of Jesus, to the worship of Jesus, how to repent from nationalistic Christianity, to living aligned with Christ himself, how to repent from complacency with the status quo, to a sense of urgency and purpose when the kingdom that is near seems oh so long in coming. We need to learn to follow what Bishop Michael Curry terms, “The Way of Love.” His book Love Is the Way: Holding onto Hope in Troubled Times, tells his own story, and offers us some glimpses into the lives of those who have shaped his own faith, as well as thoughts on how keep ourselves rooted in the way of love. Some of you were born into the arms of faith, you were passed from pew to pew before you could walk, you knew Jesus loved you before you could talk. Some of you left church when you left home for work or college and returned a decade or more later. Some never left. Some never returned but still love Jesus. Some came stumbling to church from recovery programs. Some came after loss in the shadow of grief. Some came because their spouse did. Some came for their children. Some came for the music. Some came because of community outreach. Some came for no particular reason they can name. We’re all here for different reasons, but we’re looking, and maybe finding, something here that’s hard to find elsewhere. And in the sharing of our stories, our faith journeys, no matter how dramatic, no matter how mundane, we glimpse ways of being beyond our own experience, we develop relationships that reach beyond barriers, we come to trust one another and ourselves and we learn to see signs that point to God. So let us tell one another our stories. This is how we follow Jesus. This is how we fish for people.

0 Comments

A meditation on the Annunciation, Luke 1:26-38, for the community of St. David of Wales Episcopal Church on the Fourth Sunday of Advent.

Growing up, my family had a set of paper angel ornaments that we put on our Christmas tree each year. They stood about two inches high with yellow curls stapled to their paper heads and gold paper wings stapled to their backs. Some held guitars, some autoharps like my teachers played, but my favorite were the singing angels who held white microphones with red tips right in front of their chests with pipe cleaner hands. I made it my job to unpack the angels, and the year my parents divorced, while I waited for my mom to come home from work so we could decorate the tree, I placed the singing angels on risers made of the empty ornament boxes, separating the altos from the first and second sopranos, and sang for them, a one-girl choir belting out every Christmas carol I knew. And I knew quite a few, having memorized many popular carols to the fourth verse. The December I was 21 and newly married, my mother gave a third of her ornaments to my sister, and another third to me. When we sorted the faded paper angels, my mother said the instrumentalists were playing mandolins and harps. I hadn’t guessed the instruments quite right, and that was okay, but when we came to the microphone angels, both my mother and my sister laughed and insisted the angels were holding candles, pointing to red tips they said were obviously flames. As soon as they said it, I saw how wrong I’d been all those years. I was a bit disappointed when I hung mute angels from my tree, but I sang the carols for them anyway. The songs touched something hidden deep within me, something I would later understand as the life of the soul. At that point in my life, I was curious about God but cautious. I didn’t want to get too close or personal. I wanted my angels to carry microphones, to fly around the neighborhood, sing out good news, and give me direction from a nice safe distance that didn’t require any action on my part. But as the years went by, and God came closer into my life, my thoughts about those candle carrying angels changed. I no longer saw them as mute and boring. I’ve always been afraid of fire. I never liked to light matches to start pilot lights or campfires, and I realized that to become a candle-holding angel, you have to strike a match and lean in close to the flame, you have to stay with the fire, hold steady, and act with care. You have to be brave and intentional in an act that’s ordinary and unglamorous. And in doing so, you help others to see. And so I’m thankful for the appearance of angels this Advent, this season of casting light into the darkness, this time of anticipation, of looking forward to a birth that’s come, and comes again, anew. And in today’s Gospel reading, we have the arrival of the angel Gabriel. He arrives without instruments, microphones, or candles, but his message cannot be ignored, even if it is not easily understood. “How can this be?” Mary asks as she considers what it means to find favor with God. I’m amazed that Mary has the presence of mind to speak up and ask questions. Impressed that she didn't run screaming, or cower under the bed. My fight, flight, or freeze response would’ve been firing away. But Mary takes it all in. Here comes an angel — cause enough for fear and trembling on his own — and then he offers an announcement to a small town teenage girl that God is going to break into human history through her, not some powerful king or ruler. An ordinary, yet extraordinary, young woman will carry and deliver God’s child. Can’t you just hear my paper angels dropping their microphones at the news? Two thousand and some years later, our jaws no longer drop at the absurdity, we’re so used to this story. Over the centuries, we’ve immortalized it in scripture, and art and music, in the carols I liked to belt out along with my angel ornaments. We’ve tamed it with familiarity, painting Mary as meek, mild, everything as peaceful and orderly as a Thomas Kincaid painting. But when we peel back our familiarity, and the comfort we have in knowing the history of these events, the whole idea seems preposterous. It’s crazy that the Creator of the Universe would plan to redeem creation by sending a baby to a poor and vulnerable young woman and her fiancé, an ethnic and religious minority couple living under occupation of an empire, forced to travel for a census and taxation. A couple who will soon become homeless refugees, forced to give birth in a stall with animals, and then hide out in another country while an army combs the countryside killing any baby that might possibly be Mary’s. Though she had no idea about any of this when Gabriel appears to her, we can feel the weight of Mary’s yes. The gravity of her consent. The courage in her words: “Here am I, the servant of the Lord; let it be with me according to your word.” Who among us would say yes with such conviction? My tendency, if I didn’t say, “No thank you,” immediately, would be to say, “Can I get back to you? I need some time to think about this.” I would try to be logical, making a pro and con sheet loaded with facts, driven by logic. And it’s doubtful my calculations would lead to a yes. Those lists never seem to lead to risking a “yes.” They keep us in “no.” Thankfully, faith isn’t logical. As the author of the Letter to the Hebrews reminds us, “faith is the assurance of things hoped for, the conviction of things not seen.” Mary is our model of that deep faith. Her journey affirms what we already now: love always involves risk and suffering. This year, the darkness of the season at our latitude has been magnified by the shadow of pandemic disease as we stay separated physically from one another, forgoing our usual holiday festivities. We hope for things unseen. The time when we can visit our families; a vaccine to curb the pandemic; healthy people, a healthy planet, and robust economies. Now, more than ever, we need to take heart and hope from Mary’s words and actions, from her wondering how this can be, and her boldness in saying yes to what she doesn’t yet understand. As we wonder what comes next, as we ask, “how can this be?” as we live day by day with more questions than answers, may we find hope in the visitation of angels, in the messages flickering in their candlelight, and booming from their microphones. May we listen to assure us not to be afraid. May we ponder the miracle of Christ’s advent, his arrival, again and again, into a broken and weary world need of healing. And let us remember the promise of the Angel Gabriel: Nothing is impossible with God. A Reflection on Matthew 25:1-13, The Parable of the Bridesmaids

Delivered at St. David of Wales Episcopal Church, Shelton WA November 8, 2020 When I read this parable for the first time as a new Christian in the mid-1980s, the end of the world through nuclear war weighed heavily on my mind, and my newfound faith in God didn’t offer any comfort when I encountered this scripture passage. I wasn’t yet part of a faith community and I didn’t know how to read the Bible any other way than literally. Jesus said, “Keep awake,” and I’d kept awake all my life plagued by insomnia as far back as I could remember. My father, a deputy sheriff, patrolled the streets all night, and I cowered under my covers at six, seven, and eight, afraid of intruders without him home to protect us. At age ten and eleven, alone overnight with my little sister, I tossed and turned all night, terrified of intruders without my mother home to protect us. “Keep awake,” Jesus said. But my childhood vigilance couldn’t guarantee anything except exhaustion the next morning. I didn’t expect anything different as an adult. In my mid-twenties, I still lay awake in fear most of the night, if it wasn’t Armageddon, it was that my husband would leave at the slightest disagreement. I could keep awake away all night, but I still wouldn’t know the day or the hour that the world would explode, or my own life implode. Living through three parental divorces before I was fifteen and, having each one come as a complete shock, I knew I belonged with the foolish and unprepared bridesmaids. I knew which side of the door the nuclear holocaust and the second coming would find me on. Now, in thirty-five years as a believer immersed in communal faith, worship, and study, I’ve learned something about the Bible, how it was written, and the varying contexts for its content. I’ve come to understand it not as an encyclopedia or repair manual, but as an ongoing conversation with God and the prophets, psalmists and apostles, Jesus and readers over the centuries. So, when I discovered that the Parable of the Bridesmaids was the gospel lesson for today, I was thankful for the opportunity to redeem this troubling passage and to form a new understanding of its meaning. I turned, as I always do, to articles from writers, preachers, and theologians for their thoughts on the scripture. I was surprised, and a little relieved, to find that everyone I consulted struggled with this parable. In her essay at Journey With Jesus (.net)*, Reverend Debie Thomas, Director of Children and Family Ministries at St. Mark’s Cathedral in Palo Alto, CA, writes: I’ve never liked the parable of the ten bridesmaids. When I first heard it as a child, I annoyed my Sunday School teacher by asking all the “wrong” questions in response: why do the bridesmaids have to bring their own light to a wedding reception? Why are the “wise” bridesmaids stingy and mean? Why doesn't the groom show up for his own wedding until midnight? Why does the bride — whoever she is — put up with such a ridiculous delay? Where even is the bride in this story? And why, after keeping his poor bridesmaids waiting for hours, does the groom blame them for lateness — and shut his door in their faces? “In all honesty,” she says, “these questions still bother me.” They bother me, too. I suppose some of the wedding logistics would make more sense to us if we lived in first century Palestine. We’d know what role the bridesmaids were expected to fulfill and what sort of delay the groom might have encountered that would’ve been long enough to put all the bridesmaids to sleep. I can only extrapolate from my own experience. When I got married as a college student thirty-eight years ago, my husband and I ordered tuxedos from Sears to save money. On the wedding day, when one of his groomsmen went to pick up the order, Kevin’s tux was nowhere to be found. After fruitless phones calls and spread-the-blame-run-around, he was finally presented with a hastily tailored ill-fitting outfit pulled off a mannequin. During the delay, I sat with my dad inside an air conditioned building (unlocked only for us by an acquaintance), but everyone else stayed put at their stations and on folding chairs inside an arbor. The guests and wedding party sweated in the August heat as 1 p.m. came and went and the clock inched toward 2 p.m. Some worried there wouldn’t be a wedding at all, thanks to a groomsman who thought it’d be funny to say Kevin had cold feet rather than nothing to wear. Through it all, none of my bridesmaids fell asleep, and none wandered off to a restroom to restyle her heat-wilted hair, or drove to the nearest 7-11 for a cold beverage. Everyone was a little thirsty and bedraggled when it finally came time to process. But everyone was there. Everyone stayed. And for all the questions and interpretations this parable raises, for all the wrestling with the literal and metaphorical meanings of the over-prepared but stingy bridesmaids, of minimally prepared and flighty bridesmaids, of the never mentioned bride, and of the woefully tardy and arguably cruel groom, it is what happens to those who’ve fallen asleep once they wake up that intrigues me. It is the possibility of staying that shimmers in my mind as I encounter the scripture today. What if the bridesmaids who were running out of oil stayed put and were there to welcome the groom in the sputtering lamp light as their oil ran dry? What if they stayed even if that meant being seen with all their faults on display and having to admit to their failures? What if the oil-poor bridesmaids stayed and seeing their plight close up, the oil-rich bridesmaids had a change of heart and shared from their flasks? We can never know the hour or the day (sort of like this week as we waited for election results). And so far, the waiting for Jesus’ return continues. So, what if we accept the inevitability of falling asleep sometimes? And what if learn to keep awake in anticipation rather than fear? What if we say yes to the wedding invitation and come just as we are? What if God wants only us, and our inner light, not what light we carry in our hands? What if together, we all learn to dance in the dark? What if? *For more of her thoughts on this scripture, I invite you to read Debie Thomas’s reflection. Photo by Thought Catalog on Unsplash

Ars Poetica is in its ninth year here on the west side of Puget Sound. Poets living in Kitsap, Jefferson, and Mason (that's me) Counties submit up to three poems to a jury of local artists who choose one or more poems to interpret in their chosen medium. When complete, the art is displayed in participating galleries, and usually culminates in author-artist events at the galleries, where the poets read their poems standing alongside the artwork inspired by their poems, and the artist speaks about his or her creation, and how the poem inspired it. This year, of course, everything is different. The events never took place, and most of the exhibits were cancelled. Thankfully, a number of poems and the accompanying artwork are on display during the month of September at the Poulsbohemian Coffeehouse in Poulsbo, WA. In addition, local artist Bev Hanson has put together a virtual exhibit of the Poulsbohemian exhibit, features statements from both the artists and poets. I love the watercolor that accompanies one of my poems: Outside My Window Outside my window in early morning fog eagle finds a salmon bleached in decay washed ashore the day before lays claim with anchored talons rips flesh with razored beak until it sees me looking out from behind glass too close for its comfort flaps its mighty wings flies out of view holding fast to the fish I walk to the kitchen for breakfast one life feeds another Why I chose this poem: Artist Andrea Tiffany.

Birds seem to provide my greatest source of inspiration to paint, followed closely by the local landscape of mountain- framed saltwater. Fish often come popping up to the surface of my artwork, as well. This poem contained all I needed, and though Eagles are not my favorite bird—a bit brutish, for my taste—they are spectacular creatures, and the partnership between Eagles and Salmon is a local classic. Media: Watercolor Price: $200 What inspired me to write this poem: Poet Cathy Warner Two-and-a-half years ago I moved to low bank fixer upper in Union on Anna’s Bay of the Hood Canal. There is always something to see out the window. At low tide, the bay is mud, oyster beds, and the Skokomish River. When the salmon run, occasionally a dead one washes ashore. This particular morning, I stumbled into the living room to find an eagle unusually close to the house feasting on a salmon. I think both of us were startled by our nearness to each other.” Enjoy a PDF of the entire virtual exhibit here. Midnight May 31, 2020

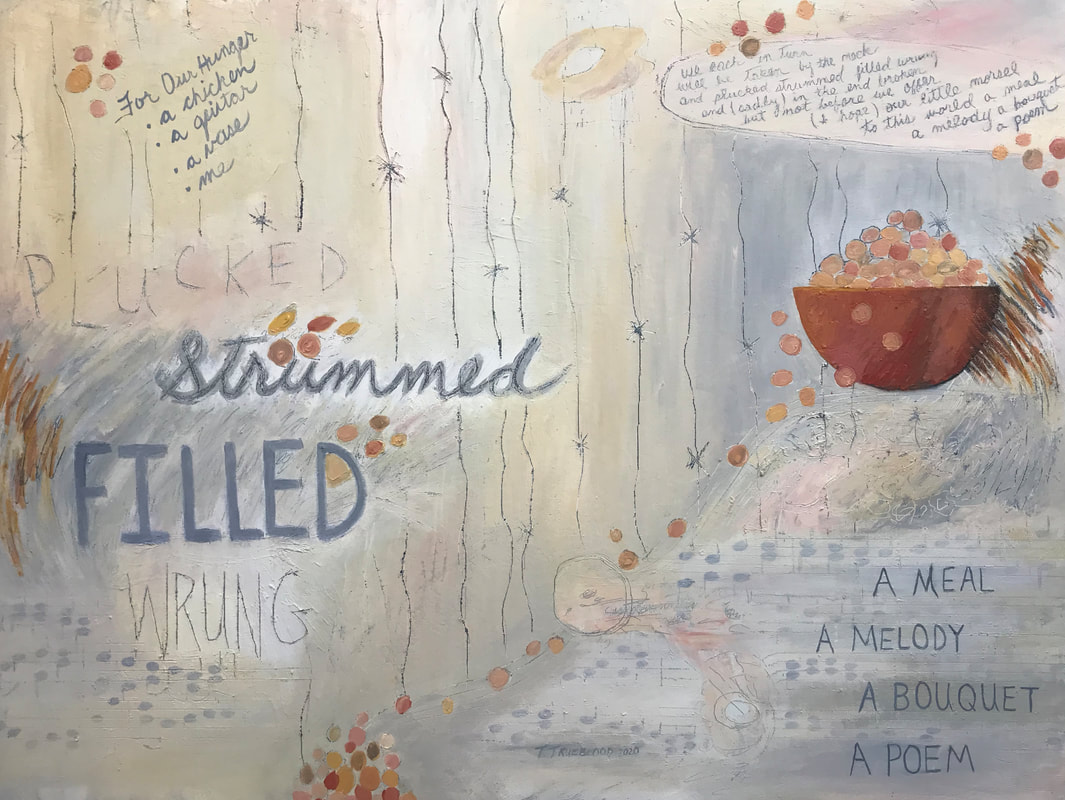

If a poem could keep the world from exploding, other lives from imploding I’d never put down my pen. I’d ink blank pages until fingers cramped, blistered, and bled, until the marks of artistic suffering smeared the alphabet of good intentions. I’d write until compelled to stop and look upon the streaked mess I’d made of creation. Forced to cease my frenetic struggle for self-expression I’d rub a tired hand across my neck and just breathe in and out because I can live in the present moment. I’d see tears of privilege smear my careful pages forming corona bursts that spread like wildfire consuming poetic constructs. Ink seeping into blood bleeding into grief that overflows its banks surging with despair flooding foundations that were supposed to protect our fragility but crumble under the weight of oppression. Exposing the rotten materials upon which we’ve built systems that promise to uphold everyone but never could support the weight of equality and that fail all of us now as illusions of protection and safety collapse. The walls tumble down and we are broken, shattered scattered along the streets cowering in quarantined homes victims of an unseen virus, supremacy, and privilege. Barely masked vitriol is such flimsy covering against what we truly need to face. I should be standing alongside those destroyed by the shadow side we once tried to hide but are now parading and tweeting. Our naked underbelly celebrated our worst selves shined up our deepest fears inflicted upon others we dehumanize in order to keep our motives unexamined our wounds unhealed. My voice is so easily spoken my words so easily heard my views so easily accepted my pen so easily plied. But you who’ve been silenced you who’ve been ignored you who’ve been shunned-- protest. Riot if you must. Burn your truth into my skin and may your cries haunt me to the grave. Tarah Trueblood, one of my dearest friends, has interpreted my poem "For Our Hunger" as a 36" x 48" oil painting for her fine arts studies at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio. It's a privilege to have a talented artist and thoughtful human engage so deeply with my poetry. Reading about the creative process Tarah engaged in as she visually represented her meditation on the words and structure of the poem enriched my understanding of my own work. It's also nice to know that visual artists, like writers, compose in drafts, returning to the work and changing it.

Enjoy the poem as well as Tarah's painting "For Our Hunger" (above), and her artist statement below, which provides a fascinating a glimpse into the role of creativity in her life, as well as detailing the creative choices she made for this painting. For Our Hunger a chicken a guitar a vase me We each in turn will be taken by the neck and plucked strummed filled wrung And (sadly) in the end broken but not before we offer (I hope) our little morsel to this world a meal a melody a bouquet a poem –Cathy Warner Tarah Trueblood’s Artist’s Statement About three years into my decade of practicing law in Sacramento, California, I realized I had cut myself off from the act of creating—of giving birth. I needed a creative outlet. One autumn I signed up for training to become a docent of the Crocker Art Museum. Every Monday morning for an entire academic year I slipped out of the law office and into the magic of the Crocker. There I was immersed in color, texture, landscapes, portraits, sculptures, abstractions, history, culture, artists, and meaning-making. My favorite room became the modern art gallery where I would sit for long periods of time--entering a canvas, dialoguing with the artist, creating meaning and story. Then, my sister was diagnosed with a life-threatening blood disease that destroyed her liver. While she was on the liver transplant waiting list, I created my first watercolor painting—more like a meditation really. Today, that is one of my favorite paintings and I named it after the name of the blood disease, Polysythemia—meaning too many red blood cells. The painting is dominated by chaotic forms and bloody shades of red. Yet, in its chaos, there is a large form that strongly resembles a fetus. My sister is still living and so is her daughter who was born shortly after Polysythemia was painted. My sister’s illness inspired me to quit the practice of law in pursuit of something more meaningful. I chose to attend seminary in Berkeley to study theology, social justice, the arts, and meaning-making. That led to a career in higher education working with students to engage in the existential questions of life. Therefore, it is probably no surprise that for my painting class at Miami University, I chose to make a work that creates an experience of beyond, transcendence of the psychological consciousness of Same. The content is drawn from the poem “For Our Hunger.” My first draft attempted to preserve the short lines and stanzas of the poem which resulted in a rigid visual grid. I began to eliminate the stanzas and line breaks to shift the focus to the visual content. Ultimately, the goal was to communicate through content the poem’s meaning: life is full of hardship and yet we may discover ways to forge our suffering into beauty that nourishes our souls. Here are the choices I made to that end:

See more of Tarah's art at her Facebook page Trueblood Art Studio. Ars Poetica is in its ninth year here on the west side of Puget Sound. Poets living in Kitsap, Jefferson, and Mason (that's me) Counties submit up to three poems to a jury of local artists who choose one or more poems to interpret in their chosen medium. When complete, the art is displayed in participating galleries, and usually culminates in author-artist events at the galleries, where the poets read their poems standing alongside the artwork inspired by their poems, and the artist speaks about his or her creation, and how the poem inspired it. This year, of course, everything is different and the displays as well as events have been canceled. Fortunately members of the Bainbridge Island Photography club have been connecting via email with the poets whose words they interpreted. Here is the beautiful digital photograph created by Chuck Eklund in response to my poem, "Drifting to Sleep." Drifting to Sleep We gather behind the curtain of imagination waiting in the wings as the orchestra conducts its overture before crimson velvet All our cares flutter toward the sky as our dreamtime ballet begins How quickly the fantastic takes shape beneath our star-fused eyelids galaxies glide through our minds like ballroom dancers spinning tales across the glittering floor and the universe bursts into story Here's what Chuck Eklund has to say about his art: This photo is set in Lake Brienz, in Switzerland. We hiked around the lake and spent the night in the village of Brienz. Even though it was summer, during the day it rained on the lake and snowed on the mountains. Amazing. The building, mountains, and growth are all around Brienz. The stars were beautiful that night. However, I didn’t have a tripod and could take only a limited exposure with camera balanced on a towel on a wall. No way to get the stars. The stars and Milky Way are from Idaho. I have always regretted not getting the stars in Brienz. Your poem made me think that I would combine the two images. Thank you, Chuck, for making such a beautiful photo. I definitely feel the flight into the dream realm as my eye is drawn to the upper edge of the photo. I'm glad we could share this virtually. In German, they call today Karfreitag (Sorrowful Friday).

Here's a poem I wrote in response: Bowl of Sorrows On Good Friday 2020 This morning I place an empty bowl atop my coffee table a vessel in which to pour our suffering and sorrows -- our beloved dead we cannot mourn together our ill and dying lying in isolation our elders in lockdown waved to from windows our incarcerated overcrowded and incited to riot our perilous pre-existing conditions our harrowed healthcare providers working in horror our first responders risking their families our homeless without a place to call or stay home our immigrants and refugees who can’t find refuge our fear of black men wearing masks our fear of everyone unmasked everyone who lacks the privilege to shelter in place the classrooms closed field trips furloughed the commencement ceremonies unscheduled the valedictory addresses vanished the college tours cancelled libraries locked the athletic seasons suspended the wedding festivities forgotten the dissolutions of marriage delayed the tempers flared the doors slammed the abuse behind curtains closed ever tighter the mutual understandings unraveling the first loves by distance fractured the workplace identity whittled away the blurred boundaries between work and home the emptying pantries and pocketbooks the layoffs and lost jobs the indecipherable applications for assistance the travel plans terminated border barricaded the birthday parties banished the beaches bunkered campgrounds closed the worship services via wi-fi the hugs held hostage smiles masked the stress-snacking and viral insomnia the gray roots exposed the ends splitting the things I cannot even think of The heartbreak of being healthy and happy the shame of sacrificing nothing for my safety No grief is too insignificant to acknowledge or too monstrous to mourn When Jesus suffered the unspeakable he pleaded for our pardon Before it was finished he fashioned a family Together we carry this bowl of sorrows I had a memoir writing workshop scheduled next Saturday and was looking forward to leading the participants in one of my favorite exercises: using smells to spark our memories. I usually have a variety of items available to sniff before we write, but wanting to be cautious here in Washington state, I decided to come up with a list of smelly items rather than bring the items themselves. That way, we wouldn't all be touching the items. But yesterday, I cancelled the workshop, a prudent decision coupled the widespread closure of schools, libraries, worship services and offices in my region.

Many, many of us will now find our activities being curtailed for several weeks at least, and I'd like to do my small part to provide an alternative to the anxiety of the news as we stay close to home in the form of a creative writing exercise. Here is my "smellphabet" list of fragrant (some pleasant, some not) things in alphabetical order. I hope you'll find something on the list that reminds you of a time and place in your own life. If you do, take a few minutes to jot down the story (somewhere between 5 and 20). Once you've written your memory, I invite you to share it with someone. Was there someone else in your memory that'd get a kick out of reminiscing with you? Email them the story, or give them a call. You are also welcome to post your story as a comment here, or email it to me. I'll be sure to respond with encouragement! A Smellphabet ~Compiled by Cathy Warner A Air freshener, asparagus, ammonia B Baby powder, baking bread, bubble gum, bleach C Chanel No. 5, cigarette smoke, cough syrup, cinnamon, cabbage D Diaper Cream, Dove soap, dog (wet) E Eucalyptus, eggs, earth F Fish, forest, formaldehyde, Fritos G Grass, grape (artificial), ginger, gardenia, gasoline H Hairspray, hay (wet), ham I Illness, Irish Spring soap, icing J Juicy Fruit gum, juniper, jasmine K Kelp, kirsch, kabab L Lysol, lavender, lacquer M Mint, mouthwash, maple syrup, menthol N Narcissus, naan, napalm O Oranges, olive brine, onion P Puppy breath, Playdough, permanent marker, pencil dust Q Quince, quinine, Quaker oats R Roses, rain, rodent droppings, red wine S Spray paint, sauvignon blanc, skunk T Thanksgiving turkey, tobacco, tires, tar, turpentine U Urine (animal or human), udon noodles, urethane V Vick’s Vaporub, violets, vomit W Windex, wax, Windsong perfume X X-14 spray, Xerox copies, xylitol Y Yeast, yard clippings, yogurt, yam Z Zoo, Zippo lighter fuel According to neuroscientists, smells have a stronger link to memory and emotion than any other sense. Read more about that here. |

I began blogging about "This or Something Better" in 2011 when my husband and I were discerning what came next in our lives, which turned out to be relocating to Puget Sound from our Native California. My older posts can be found here.

Categories

All

Archives

September 2023

Newsletters |